Research Assistants: Rohit Singh, Alex Schwarz, April Anderson, and Danhua Zhang. Funding for this project was provided by the Weissman Center for International Business, and is gratefully acknowledged.

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. is the world's largest retail enterprise, with total revenue of $421.8 billion and a net income of $16.4 billion in 2011.1 It is also the world's largest employer, with 2.1 million employees worldwide in 20102—not including workers hired by its suppliers. In my view, Wal-Mart provides a prism through which to examine how many multinational companies (MNCs) engage in illegal and unethical behavior. They use their bargaining power and market control to pressure countries to condone environmental degradation and violation of national labor laws.

In the United States, since 2005, Wal-Mart has paid about $1 billion in damages to U.S. employees in six different cases related to unpaid work.3 Moreover, Wal-Mart opposes any form of collective action, even when employees are not seeking unionization, but simply more respect.4

Overseas, the company has been embroiled in a series of scandals, including multiple cases of bribery. In April 2012, The New York Times published a story that uncovered hundreds of suspect payments to Mexican officials, totaling more than $24 million.5 According to the Times, Wal-Mart received hundreds of internal reports of bribery and fraud every year. In Asia alone, there had been 90 reports of bribery in the previous 18 months.6 Since the spring of 2011, Wal-Mart has spent over $35 million and hired more than 300 outside lawyers, accountants, and investigators to investigate and deal with bribery issues.7 Wal-Mart's penalties under Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Securities and Exchange Commission regulatory filings are likely to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, yet this is unlikely to act as a deterrent for the future. Even the worst-case scenario of $1–2 billion in penalties would represent a small fraction of Wal-Mart's earnings.

Worst of all, Wal-Mart—and other MNCs—can be connected to the deaths and injuries of hundreds of people in workplace accidents, most recently in Bangladesh, but also in other countries where low-skill, low-wage manufacturing predominates.

Bangladesh Garment Factory Disasters

Bangladesh is the world's second largest garment exporter after China. Its foreign exchange earnings of $19.1 billion in 2011–2012 represented 13 percent of the country's GDP and 78 percent of annual exports. The country expects to triple its garment exports in the next three years as worker wages increase in China and more production migrates to Bangladesh.8 Bangladesh has no natural comparative advantage in garment manufacturing, hence it has been unable to create complementary industries and diversify its manufacturing base. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that these low prices are obtained through low wages and unsafe working conditions.9

The minimum wage for garment industry workers is $37 a month,10 one of the lowest in the world. The situation is so bad that local factory owners have complained that wages should be at least 30 percent higher, but that resistance from foreign buyers makes this impossible.11 MNCs have also put pressure on the Bangladeshi government not to increase wages or impose safety conditions—because that would raise the prices for foreign buyers.12 Meanwhile, Wal-Mart CEO Mike Duke got a 14 percent pay hike in 2012, raising his pay to $20.7 million."13

On the weekend of November 24, 2012, a fire raged at the factory of Tazreen Fashions in Dhaka, killing 111 and injuring over 150 people. A large portion of the plant's output was made for Wal-Mart, although it also produced garments for other U.S. and European brands. The plant lacked adequate fire prevention and exit systems. Furthermore, the plant's managers blocked some of the staircases, preventing workers from exiting. The factory had a long history both of unsafe working conditions and of making apparel for many of the world's largest retailers.14 Yet Wal-Mart, Sears, and others denied any knowledge that Tazreen Fashion was making their clothing. On November 26, 2012, Wal-Mart terminated its relationship with its supplier stating, "The fact that this occurred is extremely troubling to us, and we will continue to work across the apparel industry to improve fire safety education and training in Bangladesh."15

The 2012 fire was not the first in Bangladesh. On December 27, 1990, a similar factory fire killed 32 people and injured over 100.16 In all, approximately 1,100 workers have died and over 3,000 have been injured in Bangladesh since 1990. Yet MNCs have never acknowledged that their demand for the lowest possible price and extremely tight delivery schedules may have been a significant contributing factor toward lower wages and hazardous working conditions.

The deadliest incident yet occurred on April 24, 2013, when the eight-story Rana Plaza garment factory building collapsed. There were 1,127 casualties as of May 14.17 Sadly, history suggests it is unlikely that reactions to this event will lead to improved worker conditions in Bangladesh and similar countries.

Bangladesh Garment Factory Disasters (updated May 14, 2013)

Sr. No

Date

Accident

Killed

Injured

1

Apr 24, 2013

Rana Plaza building collapse

1,127

-

2

Jan 26, 2013

Fire at Smart Garment Export

7

+ 8

3

Nov 24, 2012

Fire at Tazreen Fashions, Tuba Group

112

+ 200

4

Dec 14, 2010

Fire at That's It Sportswear Ltd, Ha-Meem Group

28

+ 100

5

Feb 25, 2010

Fire at Garib & Garib Sweater Factory

21

+ 50

6

Feb 24, 2006

Fire at KTS Garments

85

+ 150

7

Apr 11, 2005

Building collapse, Spectrum Sweater & Knitting Factory Knitting Industries

73

+ 100

8

Jan 7, 2005

Fire at Shaan Knitting

23

+ 40

9

May 3, 2004

Stampede over fire in 5 companies

6

+ 30

10

Aug 9, 2001

Stampede over fire, Mico Sweater Ltd.

23

+ 100

11

Nov 25, 2000

Fire at Chowdhury Knitwear Garments

51

+ 100

Wal-Mart's Response to Mistreatment of Workers in its Global Supply Chain

Wal-Mart's January 2012 guidelines for overseas suppliers18 include compliance with local laws on voluntary labor, working hours, employment practices, wages, freedom of association and collective bargaining, health and safety, dormitories and canteens, environment, conflict of interest, and bribery and corruption. Yet Wal-Mart forbids all suppliers, their sub-contractors and primary-tertiary suppliers of materials, services, and finished products, to disclose any information about the nature and scope of their relationship with Wal-Mart, including disclosure of plant audits, and reports of shortcomings and corrective actions required.

Wal-Mart first established a factory certification program in 1992, which focused on Bangladesh and China. It has since been expanded to other countries. Since 2002, it has been supervised by Rajan Kamalanathan, vice president of Ethical Sourcing. He is also on the board of the Global Social Compliance Programme formed in 2006, which now includes more than 30 companies. According to Kamalanathan, Wal-Mart audited over 9,000 factories around the world in 2011 alone. The program has also set stricter conditions for compliance, with suspension periods ranging from 90 days to one year.

Wal-Mart's factory audits program depends on three elements: identifying all participants in the supply-chain; the foreign buyer's ability to spot shortcomings in the factory's production quality, materials, and processes; and the supply chain's ability to provide quality goods and meet strict shipment schedules, so that the company can stock its retail stores for important sales seasons such as Christmas.

Clearly, limitations imposed by the third element often conflict with the first two, forcing Wal-Mart to balance these competing objectives. An analysis of available data on hazardous working conditions and mistreatment of workers leads to the inescapable conclusion that Wal-Mart has made a Faustian bargain, sacrificing the interests of workers when they conflict with the company's needs. Retailers usually place orders through suppliers and middlemen who then try to find factories with the lowest cost. At the end of the day, retailers' only concern is that the price stays low.19 Middlemen provide foreign buyers with an easy escape from factory-related problems, as they can deny any knowledge of these factories.20

Consider this excerpt from an interview with Kamalanathan: "If a supplier or an agent chooses to subcontract without informing us, then that is a problem. We can put all kinds of controls in place, but if they don't tell us where they're putting our order, then that is a problem."21

In a similar vein, in December 2012, Wal-Mart's CEO Mike Duke asserted "We will not buy from an unsafe factory and if a factory is not going to operate with high standards, then we would not purchase from that factory."22 And yet, just two weeks prior, a top Wal-Mart executive acknowledged in an email to a group of retailers that the industry's safety monitoring system was seriously flawed.23

Following multiple incidents of fire-related deaths and injuries, industry leaders, government representatives, local garment manufacturers, and trade union leaders met in Dhaka in April 2011 to discuss providing financial help to local factories to pay for the cost of improving safety conditions. But Wal-Mart declined to participate because it would increase the company's costs. A senior official of Bangladesh's Ministry of Labor and Employment indicated that Wal-Mart's response effectively scuttled any positive action on the part of foreign buyers.

Immediately following the April 24, 2013 building collapse in Bangladesh, there was an April 29 meeting near Frankfurt. Wal-Mart, the Gap, H&M, and other major retailers met with labor groups and NGOs to work on a plan to prevent such tragedies in future. The European Union, Bangladesh's largest trading partner, is considering sanctions.24 Yet my guess is that this will probably be “business as usual," with no concrete results.

The ultimate irony is Walt Disney's announcement that it will cease doing business in Bangladesh and transfer all future business to other countries—a step that is likely to be followed by other MNCs. Clearly, other countries would have to be similarly cost effective, which leads me to conclude that: (a) Instead of solving the problem, MNCs will seek other groups of desperate workers willing to risk their lives in the hope of finding work at subsistence level wages; and (b) Since it would be very difficult to replace the entire Bangladeshi apparel production, a more likely scenario is that MNCs will limit themselves to a face-saving gesture, diversifying their production sources somewhat, and still remaining in Bangladesh for the foreseeable future.

Wal-Mart's CSR Reports: Gap between Promise and Performance

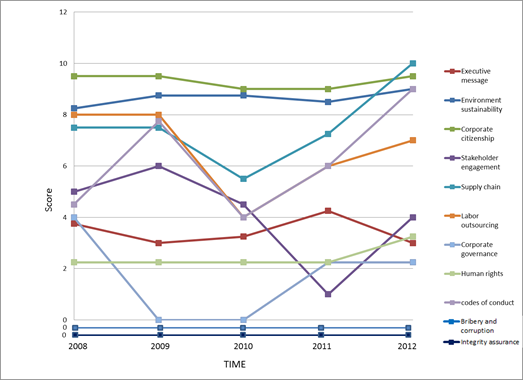

In an effort to evaluate Wal-Mart's public posture on corporate social responsibility, we examined its CSR–Sustainability reports for the period 2007–2012. This review was based on the analytical framework developed in the CSR Monitor™ at the Weissman Center for International Business. The system scores each report on 11 contextual elements: that is, subject matters covered, in terms of objectivity, materiality, specificity, and accuracy. Each CSR report is also scored as to the scope of independent external verification and integrity assurance of the information provided.

Wal-Mart scores well above average for some elements, such as environment and sustainability; corporate citizenship, philanthropy, and community relations; and supply-chain management. When it comes to environment and sustainability, Wal-Mart has focused on activities that have resulted in improving productivity and profitability. However, Wal-Mart's relatively high scores dealing with supply-chain management are somewhat deceptive, since the company provides a great deal of information on how its supply-chain elements ought to be managed, but none on how those systems have actually worked in practice. Information is even scarcer on issues like bribery and corruption, and integrity assurance (independent external verification of information contained in the CSR reports). The company uniformly scores zeros in integrity assurance through the entire period covered in our analysis.

Despite its 34-page statement of ethics, Wal-Mart's corporate culture is dominated by financial considerations to the exclusion of ethical concerns. The value-set of large corporations and their leaders are largely insulated from general societal values. An increasing gap between high-wealth and high-earning groups and low-wealth and low-earning groups means that top earners find little in common with other groups. Equally important, corporate executives measure their actions against the standards of their peers, fully confident that their behavior will be condoned and protected by their peer group, and their powerful friends in government and other social segments.

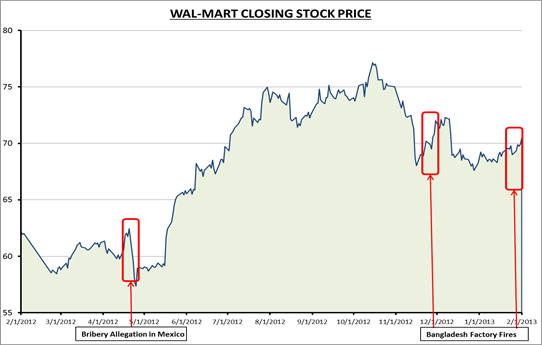

Indeed, while Wal-Mart's share price had a precipitous decline for a couple of days following the disclosure of bribery in Mexico, it soon recovered. Share prices also fell, though to a lesser degree, after the 2012 factory fire in Bangladesh and then recovered.

Will the World of Wal-Mart Ever Change?

It is highly unlikely that any meaningful change will occur in the near future. Evidence of sweatshop-like working conditions has been around for over 20 years in low-wage, low-skilled industries, yet MNCs' business model makes them relatively immune to pressure from their financial ecosystem: shareholders, senior management and potential investors. The situation is not terribly different with regard to external stakeholders.

One of the most important obstacles to change is Wal-Mart's business model, with its foundation in everyday low prices. This strategy imposes severe limits on any price increase, for fear that competitors will take away its market share. At the same time, Wal-Mart must generate comparable return on equity to satisfy Wall Street and potential investors. Therefore, growth in profits must come from expansion of business activity throughout the world at the fastest possible rate (even if by illegal means), and from procuring goods and services at the lowest possible prices; hence the use of sweatshops and hazardous working conditions that contribute to the lion's share of Wal-Mart's profits.

Therefore, the only noticeable change has been in the polished responses of righteousness and defensive self-criticism regarding the miseries inflicted on workers, without even remotely acknowledging responsibility. Even the media and civil society organizations (CSOs) have developed a sense of defeatism which accepts this "new normal" as a "fait accompli." Like every company, Wal-Mart faces external pressures in the marketplace: customer loyalty, industry best practices, expectations of major shareholders and investment community, CSOs, and increased government pressure and regulatory oversight. However, these external pressures to date have been relatively benign. Yet despite extensive media coverage, demand for Wal-Mart's products continues to grow. In most industrially advanced countries, product boycotts by consumers have been short-lived, except for products seen as threats to consumer health and safety. Public pressures and media coverage tend to blow over. Wal-Mart does not have to fear its competitors either, because they all use factories with similar cost structures and labor practices.

In the past, institutional investors, notably public employee pension funds, have been aggressive in filing proxy resolutions requiring companies to be more transparent about their activities in China and other low-wage countries and to initiate measures to improve conditions. However, these voices have become mostly muted because objectionable activities have become the norm rather than the exception, which makes it difficult for institutional investors to use their stockholdings in dividend companies as a lever for change. For the same reason, CSOs have also become reluctant to mount efforts to seek proactive responses from companies.

In the long run, however, the status quo is surely unsustainable. Even if consumers continue to flock to the lowest prices, there is growing unrest in the low-wage countries that supply these goods.

What is the effective way to bring about change? Consumers should certainly put more pressure on retailers to ensure that their goods are produced in safe conditions, for fair wages. In addition, we suggest that institutional investors concerned with long-term risk to their investments should acquire sizable equity interest in a small group of corporations with significant supply-chain operation in low-wage countries. The shareholders could then exert pressure on these companies to:

a) Ensure that they fully comply with their company's code of conduct and have that compliance maintained and verified;

b) Code compliance should be monitored by the board audit committee, which would take appropriate action in case of incomplete or poor compliance; and

c) The company could then use successful compliance to build corporate reputation and sustainable growth. This would give it a competitive advantage in entering new markets—both as a source of product purchases and also in building a consumer franchise in those countries.

We believe there will come a day when it will be in the self-interest of MNCs like Wal-Mart to stay within the law and to treat their workers humanely. We all have our part to play in making this happen. But sadly, that day is probably still far off; if the past is any indication, it will be a long time before real change comes to the world of Wal-Mart.

NOTES

1 CNN, “Global 500," CNN Money, July 25, 2012.

2 Christopher Matthews, "10 Ways Walmart Changed the World," Time Magazine, July 2, 2012.

3 Ira Boudway, “Labor Disputes, The Walmart way." Bloomberg Businessweek, Dec. 13, 2012. See appendix table 5.

4 Susan Berfield, “Walmart vs. Union-Backed OUR Walmart," Bloomberg Businessweek, December 13, 2012.

5 David Barstow, “Wal-Mart Hushed Up a Vast Mexican Bribery Case," The New York Times, April 21, 2012.

6 Ibid.

7 Stephanie Clifford and David Barstow, “Wal-Mart Inquiry Reflects Alarm on Corruption," The New York Times, November 15, 2012.

8 Archim Berg, Saskia Hedrich, Sebastian Kempf, Thomas Tochtermann, McKinsey & Company, “Bangladesh's ready-made garment landscape: The challenge of growth," November 2011.

9 Björn Claeson, Deadly Secrets: What companies know about dangerous workplaces and why exposing the truth can save workers' lives in Bangladesh and beyond (DC: International Labor Rights Forum, 2012), 14.

10 The New York Times Editorial Board, “Worker Safety in Bangladesh and Beyond," The New York Times, May 4, 2013.

11 Syed Zain Al-Mahmood, "Bangladesh Fire Raises Pressure to Improve Factory Safety," The Wall Street Journal, December 13, 2012.

12 Ibid.

13 Lindsey Rupp & Renee Dudley, “Wal-Mart CEO Duke's Pay Rises to $20.7 Million Last Year," Bloomberg Businessweek, April 23, 2013.

14 Jim Yardley, "The Human Price: Recalling Fire's Horror and Exposing Global Brands' Safety Gap," The New York Times, December 6, 2012.

15 Walmart, Walmart Statement on Fire at Bangladesh Garment Factory," Walmart.com, November 2012.

16 Claeson, Deadly Secrets, 13.

17 BBC News Asia, “Bangladesh building collapse death toll over 800," BBC News Asia, 8 May 2013.

18 Wal-Mart, “Wal-Mart's Standard for Suppliers," January 2012.

19 A similar admission was made by Wal-Mart in its 2011 Sustainability Report where it stated that the company was facing problems of undisclosed and non-compliant subcontractor in China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Middle East and Africa. Similar problems were also identified by NGOs in the Thai Seafood and Cambodian apparel industries both of which are important part of Wal-Mart's supply chain. Some reports estimate that Wal-Mart's suppliers in China outsource more than half their work to unregulated sub-contractors. Solidarity Center, “True cost of Shrimp," January 2008. Community Legal Education Center (CLEC), “Corporate Social Deniability: Walmart and H&M Refuse to Take Responsibility for Kingsland Workers," 30 January, 2013. Andy Kroll, “Are Walmart's Chinese Factories As Bad As Apple's," Mother Jones, March-April, 2012.

20 Yardley, “The Human Price."

21 Jessica Wohl, “Walmart Promises to Strengthen Supply Chain Safeguards After Bangladesh Factory Fire," Huffington Post, December 11, 2012.

22 Steven Greenhouse and Jim Yardley, “As Walmart Makes Safety Vows, It's Seen as Obstacle to Change," The New York Times, December 28, 2012.

23 Ibid.

24 Shelly Banjo," Retailers Seek Plan to Prevent Disasters," The Wall Street Journal, April 30, 2013.