This essay is based on a lecture given at the USC Levan Institute on January 21, 2014, as part of the Council's Global Ethical Dialogue in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles, London, Toronto, New York, and Sydney: we call these—and many other metropolises—global cities because they have become home to populations drawn from every corner of the planet, all working within global supply chains and technology networks that are drawing the world's peoples into ever closer interdependence.

In 1960, none of these cities was hyper-diverse. By 2000, all of them were.1 There have been few changes in the landscape of moral expectation and daily life more dramatic than this and we can expect that these trends will continue throughout the twenty-first century. The UN anticipates that the world's cities—especially the 23 megacities with populations larger than 10 million—will absorb all of the 2.3 billion population increase expected between now and 2050.2 Nearly 70 percent of the world's population will live in cities by then, and we can expect that these cities will be multilingual, multiracial, and multicultural.

Global cities bring into focus a key moral puzzle in globalization: how strangers, who do not share language, culture, faith, or shared origins, develop sufficiently common moral assumptions to live together, cooperate, and, for the most part, avoid conflict. For by and large, global cities have proven to be an unimaginable success. By unimaginable, I mean that peoples who are in inveterate conflict with each other back home, share the same urban space in the global city. By unimaginable I also mean that if you had asked anyone in 1960 whether, in a city like Toronto or London, people from a hundred different cultures and faiths could share the same urban space, you would have been met with doubt and disbelief.

Some predicted disaster. In the 1960s a British politician, Enoch Powell, contemplating the prospect of London becoming a global magnet for migration gloomily quoted the nightmare vision in Virgil's Aeneid of the Roman river Tiber foaming with blood. Fifty years later, the River Thames flows through a London that is the more or less peaceful home to populations from the entire world.

What, I want to ask, are the moral preconditions for this success?

While migration has been a feature of globalization for centuries, the emergence of these global cities is essentially a new phenomenon and the moral vernacular of multicultural tolerance we use to understand it is also new. In order to see this—and situate our examination of the moral codes of global cities—we need to distinguish the globalization of our era from the globalization that has gone before.

The first new element is that it is post-imperial. Europeans no longer rule subject peoples in Africa and Asia. Trade no longer follows the flag. In a post-imperial globalization, the new normative dispensations are that no race is born to rule and all peoples are equal and are entitled to self-government. This moral code is inscribed in international law, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Charter, and while these lofty declarations are at some distance from the sometimes mean streets of the global city, they do describe a normative expectation that accompanies every migrant: whatever else they may anticipate, they are not coming to the global city to inscribe themselves in a new relation of colonial subordination to white people. They are coming, basically, in search of a better life for themselves and their children. Central to that expectation is the faith that the global city will allow them to escape the racial, social, and moral inequities of the places they left behind.

Basic racial equality is the sine qua non of life in a global city, at once a driver of expectation and, when violated, a source of conflict and also a pole of expectation around which repair and reconciliation have to be built.

The second feature of globalization follows from the first. No one state or global power, not even the United States, is securely in charge. While the rest of the world likes to believe that America, its government and/or its giant corporations control globalization, this is not how ordinary Americans commonly feel about it, especially those working in sectors buffeted by what Joseph Schumpeter called the "creative destruction" of capitalist change.3

For many Americans—and for peoples situated in less powerful states around the world—globalization is a synonym for all the malign forces of economic change they are powerless to control. The moral challenge that all human beings share is how to use the political power of sovereign states to regain control of these forces so that they serve humane purposes.

The third feature of globalization is that there is no "other," no Soviet or communist model that offers a systematic alternative to capitalism. It was the leader of the Chinese Communist Party, after all, who said in 1979, "It is glorious to be rich." If there is a single global ethic at work in the world, a single aspiration in common, that would be it.

This aspiration is at once moral and economic: to be rich, and in the process, to escape poverty and the community and religious limitations that go with small-scale rural life. The desire to get rich includes moral impulses of emancipation and self-realization that only migration to the city makes possible.

For the first time, the entire world is subject to the logic of this impulse and hence to the organizing power of the capitalist market, and its central moral premise, that a price can be put to anything we want.4 The logic of the market is all powerful, not least because money provides a medium that everyone understands, that sets prices and values among peoples who may not speak the same language or share the same moral or cultural assumptions.

The cash nexus, as Marx called it, is the universal communicative system of a global economy, but in moral terms it does not sweep everything before it.5 Every culture in the world has always set limits to what money can buy, whether it is salvation in the after-life, public offices, or emotional relationships—like friendship—that ought not to be tainted by the cash nexus. Every culture, in a globalized age where money is king, confronts the challenge of fixing limits to the power of money, to define what values are sacred, non-tradable, beyond the reach of the cash nexus.

The fourth feature of our new moral situation is that distance has collapsed. Thanks to global migration, millions live together now, cheek by jowl, in global cities. Peoples who were once kept apart by the hierarchies of empire now share the same urban space. Multiculturalism has become our shared—and problematic—moral destiny.

There are few better places to study that destiny, to explore how we manage the unprecedented opportunities and challenges of living with difference, than Los Angeles.6

Los Angeles is a capital of the world's entertainment industry, a port shipping huge volumes of goods to and from Asia, and a vast metropolitan area that has opened its doors to mass migration from every corner of the globe.7 In the space of no more than 40 years, it has become one of the most diverse cities in North America.

In the struggle to find common ground, L.A. has provided the world with extremes of conflict and examples of cooperation. The Watts riots of 1965 and the Rodney King uprising of 1992 made the city a symbol of interethnic violence and dysfunction. But these ruptures in the fabric of justice and order also offered community leaders an opportunity for reform and renewal. Since 1992, the city has become a laboratory of intercommunal coalition building.

Let us look at L.A. through an ethical lens, searching for "the moral economy," the tacit but shared assumptions about moral behavior that enable neighborhoods and communities to overcome their own internal differences and then reach out and forge links with other racial, ethnic, or national communities in the metropolis.8

To solve the central ethical problem of the global city—how to generate collaboration among strangers9—the city needs an operating system: shared moral codes that enable the millions of people, from different races, origins, and social backgrounds to live together on a daily basis. Shared interests will get them only so far. Even the "cash nexus" can only function effectively on the basis of limited trust. It is shared ethics that enable people to find common ground when their interests collide.

Ethics can be modeled as an operating system because, like software, it guarantees the predictability necessary for stable human interactions. The most important form of predictability is security: for interactions to be free from violence. Without security, trust between strangers is impossible.

In a global city, people want more than just to be safe. They want a space to experiment, to emancipate themselves from the roles they left behind in small face-to-face communities. Historically, it is the often-lamented anonymity of city life that has provided the safe space for individuals to become individuals, to find and assert identities that were suppressed in rural or village settings.

Cities have to provide safe spaces for individuals to flourish, but they also have to permit individuals to seek status and approval from strangers. Besides safety and privacy, cities have to provide opportunities for seeking, earning, and giving respect. In any anonymous urban environment, according respect to strangers is a risky and uncertain business. If you accord respect and are rejected, you recoil. In a city with a healthy moral economy, moral risks are rewarded, trust is returned, and basic reciprocity is strengthened.

In the multicultural city, people arrive with the moral operating systems they inherited from their native environment. These vary from culture to culture—Los Angeles has people from 115 foreign countries, speaking 224 different languages—and it is crucial to the civil peace that these differing cultures share a few basic rules, including prohibitions against violence, false witness, and lying, and a few positive injunctions that stress reciprocity: do unto others as you would be done by.10

These expectations may be codified in law but law alone cannot ensure that everyone complies. Ethics can be seen as an operating system because when we start up our lives every morning, our moral systems start up with us, without enforcement or top-down supervision, in the common interactions of daily life.

Cognitive psychologists and neurologists have shown that many of the shared moral reflexes in any urban operating system—empathy, sympathy, fear, and repulsion—are hardwired in our brains11 We could call these instincts moral universals except for the evidence that cooperative impulses become imprinted features of our behavior only if these impulses are rewarded by experience. We learn the cooperative behaviors required for an effective urban operating system as children, if we are lucky enough to have stable families, if our public school systems do their jobs, if our places of worship tell us how to live right with ourselves and with others.

A lot has to go right in our moral education for civil cooperation to become our second nature.

Moreover, the sources of moral learning that shape our conduct do not always speak in the same voice or teach us the same lessons. We have to take ownership of the ethical operating systems inside our own conscience. As with our computers, we personalize our operating systems, so that they allow us to share with others and serve our personal identities and needs. It is up to us to forge what we have learned and what we have inherited into the principles we live by.

Our operating systems have to contend with a lot of noise, coming from conflicting perspectives. One source of noise is the media and entertainment industry. Los Angeles itself, as the global capital of this industry, has probably done more to structure our moral imagination of strangers than anywhere else in the world. From Chinatown to Blade Runner to Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, the movies fill our imaginations with dystopian and utopian visions of city life, so that in all our actual interactions with strangers, we are working our way toward them, across the stereotypes that often create paranoia and distrust.

All of these conflicting influences structure the imagination we bring to moral life in the city. Operating systems have to filter out most of the noise, and provide us with stable expectations and guidelines. When the noise is filtered out, we don't have to make constant choices about trust in the city. The operating system we take for granted allows our moral behavior to be reflexive, unconscious, and, as long as things go well, unproblematic. Ethical life then feels like joining traffic on the freeway: almost all of the time, we can count on the other drivers to do what we expect, and they can count on us to do the same.

In the last decades, there has been an explosion of fascinating work by cognitive psychologists about how this largely automatic ethical behavior actually functions. What is at stake, whether through automatic reflexes or conscious reflection, is a constant process of evaluation and justification. We evaluate others, we justify ourselves using simple binary oppositions—fair/unfair, just/unjust—and then we struggle over the grey areas in between. Moral operating systems don't just coordinate behaviors among strangers: They make them meaningful.

They also program our expectations and our aspirations.

Central to these aspirations is the search for community. It is the key word in any moral operating system, especially in a global city.

There is no shortage of communities in Los Angeles. Some are the spatial territories we call neighborhoods, while others are faith communities. Still others are virtual communities, where, to use an L.A. example, young Muslim believers use social media to share opinions and identities in more fluid and creative ways than those allowed in a traditional mosque. These virtual communities, needless to say, start in one global city and then rapidly deterritorialize and draw in believers or adherents from other cities around the globe.

In a global city, all community is elective, rather than ascriptive; places of belonging are chosen, and this means they are fluid and constantly changing as creative or defensive responses to the challenge of surviving in the city. Just drive along Slauson Avenue in L.A. and you will see the storefront churches, black and Latino, some of them Pentecostal, one of them proclaiming "Holiness or Hell" on a sheet hung over a doorway. These are the elective communities that provide refuge, hope, and belonging. Go to the Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church for a service; listen to the University of Southern California gospel choir sing "Hallelujah," hear the call and response between preacher and congregation, and you will know what community feels like. Even at Mount Moriah, however, the community is not stable. The preacher has to hold his congregation together—many are leaving for the suburbs—and young people do not automatically elect to show up for worship on Sunday.

The question for L.A. is whether there is a community of communities, transcending and uniting the diverse peoples who make up the city.

Everybody in L.A. is searching for community, affirming it, defining it, or defending it from attack. Community has civic meanings, denoting the shared values that unite people across their differences, and it has tribal meanings, denoting the particularisms of language, culture, cuisine, neighborhood that give people a sense of belonging that separates them from others.

The salience of tribal community in any global city is so obvious—the neighborhoods where all the shop signs are in one language, where all the places of worship are for one denomination—that it would be reasonable to suppose that tribal belonging—and its moral attachments—must be stronger than any general civic attachment to the larger community of the city as a whole. Yet if we had no shared operating system, if our values—and hence our behavior—were exclusively directed by tribal affiliations and loyalties, it is doubtful that a multicultural city as complex as Los Angeles could function without recurrent conflict and violence.

Some thin, rather than thick, moral consensus, mandating limited trust, nonviolence, and a default setting in favor of co-operation, appears necessary to keep a multicultural city functioning.12 The consensus has to be thin because it has to be pluralist; that is, it has to accommodate the fact that inhabitants live in many moral universes at once, tribal, familial, and traditional ones; the ones they were born in; the ones they work in; the ones they wished they live in.

The moral operating system of the global city cannot achieve a sense of common ground by suppressing or supplanting these competing tribal allegiances or values. When races, religions, and ethnicities share space in the city and interact on a daily basis, they do not suppress their primary loyalties. In a hyper-diverse city everyone balances, as a matter of course, primary and secondary affiliations. They may live their most meaningful hours "inside" their own communities of language, race, or origin, but they also live "outside" because work leaves them no choice or because they like spending time with people different from themselves. The negotiation between inside and outside is complex, but no one would venture beyond the stockades of their inside, tribal identity unless the city's pattern of daily life succeeded in creating an expectation of fluid, peaceful, and sometimes rewarding interactions with strangers.

The complex meanings of community came into focus at a meeting with teenagers in a police station in Boyle Heights, a low-income community that is 95 percent Latino. They meet every Saturday to work on the Boyle Heights Beat, a bilingual student newspaper that serves the entire community and that they produce with the assistance of teachers and journalists from the Annenberg School at USC.13

The students come from immigrant homes, where their parents speak only Spanish, but the young people work across both languages and the newspaper they edit is bilingual. So already they are navigating between two linguistic communities, keenly aware that when they leave for college—as most are intending to do—they will take a significant step away from the Spanish world of their parents. This fact has complex meaning for them, a mixture of opportunity and loss. One young woman said she wanted to go to college so that she could return to help her community, but the return she had in mind was in a distant future and, though she tried to keep this thought at bay, an unlikely one.

When the young Latino students used the word community, they gave it contrasting meanings. "A place where you are at home," "a place where you are safe," "a place where the people know you or they know your parents or grandparents." Boyle Heights had not always been a community, they said. It had been too dangerous, but now it was safe. The women said you could go home late at night, the men said the police didn't hassle them. One 16-year-old girl, whose parents are undocumented workers laboring at a bakery on the night shift, took the definition of community beyond the present and made it into a prospective project people could share into the future. She said, "A community is a place where people are trying to make things better."

So, following her lead, a community is more than a safe place, it is also a political space, where you can work with strangers to improve the lives you share. In the case of these young journalists, their commitment to their community is to put out—and also home-deliver—a newspaper that creates the common currency of reliable information. Once people have reliable information, they can start to act together. A community has moral properties, but as Manuel Pastor reminds us in his recent book Just Growth, it has epistemic ones too: without shared knowledge, a community is prey to rumor, panic, disinformation, or manipulation.14 With shared knowledge, a community can act to defend its interests and do politics together.

Within communities, however, the battle over who defines the operating system will be competitive. Sometimes it can be ferocious. Los Angeles has known decades of gang warfare—Crips versus Bloods—with desperate citizens caught in between. Gangs are the most obvious example of a community that is entirely tribal, that explicitly rejects the very terms of the moral operating system that makes a city work. Pluralism meets the limits of its tolerance here: a global city cannot tolerate moral no-go areas, zones where strangers cannot venture without the permission of predatory enforcers, or where two warring tribal codes are fighting each other for control of the streets.

In South Central L.A., around the Stentorian Community center, there have grown up an organization of gang members who have set themselves up as an intervention team, mediating between gangs, preventing retaliation shootings, reaching out to young people and turning them away from gang life. These battle-scarred, heavily tattooed men—black and Latino alike—have done time in prison; they have watched brothers and sisters die. They know that if they don't stop now, they will end their lives in prison or die in the streets.

Their work would not have been possible unless people from other communities were prepared to fund and support it. A Better LA, a private non-profit established by sports figures and business leaders is bankrolling this experiment, paying the salaries of the interveners, backing up their training of new recruits, and insisting on metrics to measure success.15

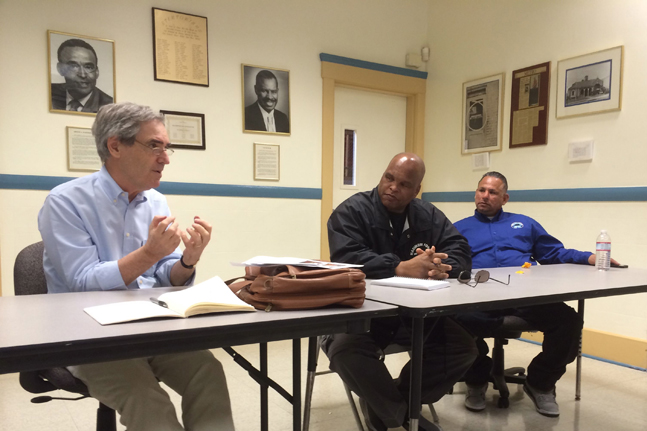

Michael Ignatieff speaking with gang mediators at the Professional Community Intervention Training Institute.

Michael Ignatieff speaking with gang mediators at the Professional Community Intervention Training Institute.

The former gang members talked about their "license to operate," a phrase that raises the question of who hands out the licenses. Aquil Basheer, one of their leaders, explained the license as a form of community consent that they secure by being known; by being disciplined, by working with the police and not against them.16 To have a license in a community is to have legitimacy. Theirs is earned through redemption. Their work is ethical—repairing themselves so they can repair others—but it is also political: trying to retake the operating system of their neighborhood from the gangs. As long as these neighborhoods are as poor as they are, however, gangs will continue to serve as an alternative belonging. Their codes will defy the operating system of the city around them. So the streets of their neighborhoods remain a battleground between competing moral systems, with the outcome still unclear.

Like the software engineers who write code for our machines, these gang veterans and the young high school students from Boyle Heights are writing code for themselves, but also for their city, because their actions, however small, are helping to change expectations, and in changing widely shared expectations, repairing the system breakdowns that keep communities apart.

We are all moral code-writers. Unlike the closed systems of proprietary software, the operating system of a city is an open system, constantly adjusting to people's lived experience of daily life. Through billions of daily interactions, as we experience the pleasure and pain of city life, we recalibrate our expectations of strangers and our own behavior.

Unlike the operating systems in machines that function identically all the time, ethical operating systems are homeostatic: they adapt to experience and they can be damaged by trauma. The riots of 1992 were one such trauma and they did lasting damage to the operating systems of the city.

In looking at how the city recovered, we can see how operating systems are repaired and who repairs them.

The police are key code-writers. When policing breaks down, when one race feels that it is systematically exposed to police violence, when others—the Koreans of L.A., for example—feel they get no police protection at all, trust collapses, communities cease to reach out and they hunker down to defend themselves.17 They learn the hard way, however, that taking the law into their own hands is a recipe for disaster. The police also learn that they cannot police without community consent.

The Los Angeles Police Department has learned from the twin traumas of the 1990s: the uprising of 1992 and the Rampart scandal of 1998.18 They have abandoned a "them versus us" fortress mentality; they have understood that, in the words of one officer, "We can't arrest our way out of any problem." Force without legitimacy cannot prevail. Legitimate policing depends on finding the religious leaders, the teachers, the parents, the local politicians who are defending the operating system of a community and then working with them to strengthen it.

Their policing methods look like public diplomacy: working with neighborhood leaders, creating relationships to anticipate trouble, and plan common interventions to solve community problems. The work is highly political, identifying leadership, making deals, forming iterative and provisional relationships of trust. These deals go beyond policing itself. For instance, they may involve brokering a commitment to a community to work with other municipal agencies to improve garbage collection or recreation space. In this process of policing as political exchange, maintenance of a shared moral operating system turns out to be crucial. As one LAPD officer put it, "Never write the community a check you can't cash; or you will lose trust."

The Boyle Heights teenagers confirmed that in at least some of their neighborhoods, Ramona Gardens for example, police and residents of the housing project do share the same operating code.

These community policing strategies seem to be working. It would be foolish to ascribe too much to a change in policing strategy, but the fact is that Los Angeles crime rates have declined for the last 15 years.19 Many communities are no longer under siege, and because they have control over their own operating system, they can reach out and make common cause with others.

An ethical operating system is like the conscience of a city. In Los Angeles, faith-based communities are among the most important custodians of that conscience.20 In the moral repair work that occurred after 1992, they were critical. After the uprising, Cecil Murray and Mark Whitlock of First African Methodist Episcopal Church had to perform contradictory feats of moral leadership: articulating the rage of their congregation, while calming them down, reaching out to adversaries, repairing the fissures that had opened up with the Korean community, while drawing together the businesspeople and politicians to fund the rebuilding of burned-out neighborhoods.

Leadership across community lines imposes extraordinary demands. Mark Whitlock was a senior executive at Wells Fargo Bank when the police responsible for beating Rodney King were acquitted. He left the bank that day, determined, as he put it, "to stop making rich people richer." Having left the bank, however, he found it difficult to establish credibility within his own community. Within a month, he was negotiating with street gangs in his neighborhood, only to discover that, as a bank executive, he was still distrusted as a "suit." Having discarded his suit, he then found himself mounting bail for a gang member arrested by the police. To work with gangs, he insisted, to respect their leadership, was not to legitimize them, but simply to acknowledge their political influence. In the global city, such unlikely partnerships between gangs and religious leaders illustrate an important nuance to the discourse of respect. Showing respect for others doesn't have to entail admiration or collusion. It simply entails cooperation in the brokerage work that enables the competition over whose operating system will prevail to stay peaceful.

In a global city, faith is both a source of the operating system's code, but also a source of conflict. Any cooperation among faiths asks believers to choose, upon occasion, between cooperation and betrayal. If Muslim and Jew, Episcopalian, Catholic, and Evangelical Christian join hands to pray before a meeting and the Evangelical evokes the blood of Jesus Christ and the agony of his crucifixion, it can be hard for non-Christians to listen to. Yet the bland alternative—"praying to whom it may concern"—leads to a betrayal of everyone's faith.

Working together to strengthen the operating system of a city can't be achieved, therefore, by abandoning authentic moral differences and identities. What is common can only be strengthened if differences are acknowledged and affirmed. What the faith-based groups have learned in L.A. is that common ground can be found so long as no one is asked to trade away what makes them distinctive.

The operating system of a city is owned by all, but its repair in moments of crisis depends critically on leadership networks rising above differences to reaffirm common bonds. Leadership cannot be taken for granted, and where it fails, operating systems can break down. Many of the leaders in L.A. are veterans of decades of community work and openly wonder who will take their place. Succession planning, getting new leaders ready, is a constant challenge and if a new generation fails to step up, networks of trust can be frittered away and communities can go backward. Moral operating systems, unlike mechanical ones, cannot function without renewal of leadership.

Ethical systems do more than keep the peace between communities. They are both operative and normative, maintaining the equilibrium of daily interactions but also pointing out what is disturbing the equilibrium and must be rectified.21 Ethical operating systems point communities towards the injustices that must be overcome together.

When seen historically, the moral economy of Los Angeles is a product of two revolutions: the civil rights revolution and the federal reforms that opened the doors to non-white immigration in the 1960s.

The civil rights revolution has run its course, but it left behind a stubborn expectation, among blacks, Hispanics, and working class whites, of equality in jobs, housing, and government services. The institutional custodians of these expectations are the faith-based groups and the unions. They work to turn expectations of equality into a reality for millions of their members.

These expectations have not been met but they are fully implanted, creating flashpoints of conflict when they are denied, but also an ongoing agenda that minority communities can unite around to advance.

Now that Los Angeles is a majority Latino city, there is a new expectation at the heart of its moral operating system: demands for a path to citizenship for the undocumented.

In Boyle Heights, the Latino high school students want to go to college, but they fear that their undocumented status will hold them back and prevent them from accessing student aid. Their situation lays bare a contradiction: on the one hand, they are told: "Reach for the stars, follow your dream." On the other, their immigration status holds them back.

Without a pathway to papers, to regularized status, students cannot follow their dreams, employers will continue to exploit the undocumented; the undocumented will be unable to maintain family ties and inequality will grow between those migrants who have secured status and those who have not.22

Without civic equality between newcomers and residents, operating systems will fracture, with communities and neighborhoods turning against each other.

As long as the issue of documentation is seen as a Hispanic issue alone, it will not be solved. The question is whether other communities can also make it their concern. Manuel Pastor, director of USC's Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, suggests how this might come about. Hispanic nannies, housekeepers, and drivers perform some of the most intimate tasks in the lives of the white middle class families they serve: they look after their homes and possessions and take care of their children and aging parents. These intimate tasks create linkages of trust, force white employers to confront the problems that their employees encounter when they are stopped on the highway without a license, sometimes driving their employers' vehicles, or when they are threatened with deportation. In this way immigration status issues become the business of their employers. These ties help explain why support for immigration reform leading to pathways to citizenship is now rising not just in the Hispanic community but among the white middle class.

When different communities make common cause on an issue like immigration reform, their cooperation is practical and pragmatic, and not necessarily a meeting of hearts and minds. What is held in common are the problems, but where problems are shared, they can be solved.

Despite these signs of cooperation, the central ambiguity in L.A. remains: whether the word community describes what is shared or what divides. Is L.A. an example of "segregated diversity" or "multicultural diversity?"23 Does the city live diversity together or do its communities live it apart?

Sixty years ago, the normative embrace of diversity was a cosmopolitan preference restricted to secure liberal elites. Now it is a value broadly anchored in the official rhetoric of city life and most people will say they think it is a good thing to learn from differences; to borrow cuisine, habits, good ideas; intermingle; intermarry; cooperate politically; and, in a word, share.

This is a real revolution in attitudes, but the test of whether it is put into practice is in how we live; in short, in our real estate behavior. Los Angeles residents, like inhabitants of all global cities, have an acute consciousness of the racial and ethnic geography of their city—which neighborhoods are white, black, Latino, Asian, in between, which ones are safe, which ones are dangerous, which ones are middle-class, which ones are up and coming, which ones are sliding down the real estate scale. People's residential choices are a practical plebiscite on whether they are willing to live among people different from themselves.

Many communities in Los Angeles are mixed: over a third of L.A. zip codes do not have a clear ethnic majority, but in two-thirds, like does cluster with like, language with language, community of origin with community of origin.24 Some of this segregation is morally innocent, reflecting patterns of immigrant arrival and self-help; some of it, however, is morally problematic in that it reflects fear, paranoia, and dislike of other groups.

At the same time, the segregation and self-segregation are extraordinarily fluid. The neighborhoods of L.A. seem to change with surprising rapidity. Groups move in, groups move out, neighborhoods prosper and decay and, as a result, while there are some desperately poor parts of the city—17.6 percent of the L.A. population lives below the poverty line—nowhere in L.A. has the ladder of opportunity entirely broken down. Someone is always moving up and moving out.25

Most remarkably, a city that is constantly absorbing new immigrants still manages to maintain a ladder of opportunity for newcomers. Forty-four percent of first generation Mexicans, born in Mexico, own their home in Los Angeles. Once they own a place, they have the collateral to move on and to move up.

"Segregated diversity" is also offset, to some degree, by intercommunal alliance building at the political level. No one ethnic or racial group has a hammerlock on power. Every candidate for the mayor's office has to put together interracial coalitions that reach across the city in order to win.

Coalitions make a multi-ethnic city governable because, when they work properly, they allow communities to share power.26 Political coalition building is crucial to the maintenance of a shared operating system, and it is one reason why Los Angeles has avoided a recurrence of the riots of 1992.

There is a larger lesson here for governance in global cities everywhere. In her recent book, The Metropolitan Revolution, Jennifer Bradley of Brookings remarks that "cities are networks rather than governments."27

When cities are as ethnically diverse as Los Angeles, they cannot be governed from the top down in command-and-control style. Instead, they need horizontal governance, with power dispersed through networks of community and business leaders all committed to the maintenance of its operating system.

These networks must ensure that no single group secures exclusive control over contracts and patronage. Favoritism can set off sparks that, when fanned, can burst into flames of conflict. Cross-ethnic political mobilization can prevent "segregated diversity" from exploding into conflict only if coalitions arrange for the distribution of patronage to be fair.

A moral economy, however, will break down unless the real economy is robust. As Detroit's travails seem to suggest, cities are bound to break moral promises to their citizens—for example over pensions and benefits—unless the local economy generates jobs and tax revenue. Los Angeles does have a broad-based manufacturing and service sector based in small- and medium-sized enterprises that provides jobs and a tax base.28 It also has robust global networks, drawing on the reach of its diaspora communities—and these continue to draw labor and capital to the city.

A recent report indicates, however, that L.A.'s unemployment rate has stayed above the national average for the past quarter-century and it is no longer creating the jobs it needs or the tax base to fund its pension liabilities.29 So the real economy is fragile, and if it is fragile, its moral economy will be too.

Central to any urban operating system is what Marx called the cash nexus, linkages between strangers expressed exclusively in the language of money.30

The cash nexus may be exploitative, but it is not lawless or amoral. Regulations limit hours and conditions of work. The Los Angeles garment sector may be a tough place to work but if a building is not up to code, it can be shut down. Enforcing labor and building standards may be a constant struggle between unions and management, with understaffed municipal authorities in between, but the battle is never over. When seen from an ethical lens, the battle is whether the real economy of a city can approximate its moral economy, basic moral expectations of fairness and justice.

In this battle, there are the pessimists, many of progressive or left wing credentials, who claim that the defense of labor standards in L.A. is a lost cause if the standards are lower in Shanghai or Manila. In an open international economy, the cash nexus imposes a race to the bottom.

Optimists would deny that L.A. is fated to lose the race to the bottom. The constant influx of immigration and its small-scale and flexible manufacturing base enable L.A. to maintain competitive advantage.

Pessimists assume that moral economies in global cities are helpless against destabilizing "restructuring" and job loss in the real economy, but this understates the capacity of citizens to shape economic conditions, especially the anarchic capacity, encouraged by city life itself, for product and service innovation by entrepreneurs and inventors that creates unexpected new pathways to jobs and growth. Many of the jobs that sustain L.A. in 2013 did not exist in 1960. Even low-wage immigrants have agency: They will only move north if they perceive it to be to their advantage. The city's steady growth suggests that immigrants still have reason to believe they gain by coming here. Over time, as they learn languages and acquire skills, they can move up the chain of opportunity. The promise of opportunity provides the moral legitimation of low-wage economies. Without that legitimacy, cities fail as moral communities.

It's time to sum up. If the logic of cooperation is to win out over the logic of conflict in the global city, these are the key institutional elements of an urban operating system:

- Pathways to documentation for all new arrivals;

- Equality before the law and fair policing;

- Interethnic coalition building in governance;

- Intercommunal fairness in the distribution of contracts and patronage;

- Open real estate ladders; and

- Open job ladders;

Los Angeles struggles to meet these criteria, but the leaders I met understand the place can't work unless these elements are strengthened.

The image of the modern hyper-diverse global city is that it is a moral jungle. Because L.A. is the capital of the entertainment industry, its creative people have done more than most to spread that image of urban anomie and dystopia to the world at large.

But the actual Los Angeles, as opposed to the L.A. in the movies, appears to give the lie to these dystopian images. Human beings do not want to live in a jungle. Los Angeles shows how deeply they strive for community, for places they can share, for people they can trust. This is not a sentimental fiction. As a matter of hard economic fact, cities simply cannot function without some key elements of a shared moral operating system: leadership networks that work to the same aspirations, share the same knowledge, that maintain solidarity between classes and races and common practices of justice and fair policing on the streets. Just keeping the show on the road is an unending struggle, requiring everyone to recommit daily to the task of seeing each other anew, cutting through the stereotypes, finding and building connections with strangers and rewriting the code that keeps our common operating system in place.

What is at stake here is more than just keeping the show on the road. When we achieve the fragile common good called community, when the real economy of a city begins to approximate, however imperfectly, the moral economy, we achieve an important victory in relationship to globalization itself. We cease to feel that we are the prisoner of forces stronger than ourselves. We cease to feel like pawns in someone else's game. To have a moral community in a city is to recover sovereignty and mastery. It is to have the sense that we can work together to shape our common life to humane, not inhuman ends. In a city like Los Angeles, ordinary human beings, in billions of interactions, struggle to turn what might have degenerated into a jungle into a moral community that every day delivers meaning, security, and prosperity to millions. This is no mean achievement.

NOTES

1 Hyper-diversity refers to populations where there is no ethnic majority and where populations are drawn from multiple immigration sources. I have taken the term from T. G. Ash, Edward Mortimer, Kerem Oktem "Freedom in Diversity: Ten Lessons for Public Policy from Britain, Canada, France, Germany and the United States," (Oxford, St. Antony's College, 2013)

2 http://esa.un.org/unup/pdf/WUP2011_Highlights.pdf

3 Joseph Schumpeter Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (London: Routledge, 1942) ps. 82-3.

4 Michael Sandel What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets ( New York: FSG, 2012)

5 Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels The Communist Manifesto (1847), part 1.

6 The visit of the Carnegie Council team to Los Angeles was made possible by the cooperation of the following institutions at the University of Southern California: the Levan Institute for Ethics and the Humanities, the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, the Center for the Study of Religion and Civic Culture, the Shoah Foundation, the Office of Immigrant Affairs of the City of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Police Department, LA Voice, and the Annenberg School. I want to thank Devin Stewart of the Carnegie Council, Dr. Lyn Boyd Judson of the Levan Institute for invaluable assistance, and Hebag Farrah of the Center for Immigrant Integration for bibliographic research.

7 H. W. Richardson and Peter Gordon "Globalization and L.A." Harry W. Richardson, Peter Gordon (2005). "Globalization and Los Angeles," in Richardson, Harry W. (ed) Globalization and Urban Development, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp 197-209.

8 See Edward Thompson "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the 18th Century," Past and Present, 50(1), 76–136 (1971)

9 Tim Garton Ash, Edward Mortimer, and Kerem Oktem "Freedom in Diversity: Ten Lessons for Public Policy from Britain, Canada, France, Germany and the United States" (Oxford: Dahrendorf Programme for the Study of Freedom, 2013)

10 These figures are in "Los Angeles: 2020. Time for Truth," a report for the City Council of Los Angeles by Micky Kantor et al., 2013; see also Roger Waldinger (1999). "Not the Promised City: Los Angeles and Its Immigrants," Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 68, No. 2, May, pp 253-272; Harry W. Richardson, Peter Gordon (2005). "Globalization and Los Angeles," in Richardson, Harry W. (ed) Globalization and Urban Development, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp 197-209.

11 Anthony Damasio Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain (New York, Penguin, 2005); Joshua Greene Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason and the Gap Between Us and Them (New York, Penguin, 2013); Steven Pinker How the Mind Works (New York, W.W. Norton, 1997)

12 On thick and thin theories of the moral good see Michael Walzer Thick and Thin: Moral Argument At Home and Abroad, (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1994)

13 www.boyleheightsbeat.com

14 Manuel Pastor and Chris Benner Just Growth: Inclusion and Prosperity in America's Metropolitan Regions (London: Routledge, 2012)

15 http://www.abetterla.org/programs/

16 Aquil Basheer and Christina Hoag Peace in the Hood: Working With Gang Members to End the Violence (LA: Hunter House, 2014)

17 Kristy Hang "The Seoul of L.A.: Contested Identities and Transnationalism in Immigrant Space" Ph.D. Dissertation, School of Cinematic Arts, USC, 2013

18 R. T. Schaefer "Placing the L.A. Riots in their Social and Historical Context", Journal of American Ethnic History, 16,2 (Winter 1997), ps. 58-63; M. Herman "Ten Years After: A Critical Review of Scholarship on the 1992 Los Angeles Riots", Race, Gender and Class, 11,1, 2004, ps. 116-135; Paul J. Kaplan, (2009). "Looking through the Gaps: A Critical Approach to the LAPD's Rampart Scandal," Social Justice, 36:1, pp 61.

19 Christopher Stone, Todd Foglesong, Christine Cole "Policing Los Angeles Under A Consent Decrees: The Dynamics of Change at the LAPD," Harvard Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, May 2009; see also L. D. Gascon "Policing Divisions: Race, Crime and Community in South LA", Ph.D. Dissertation, UC Irvine, 2013.

20 Richard Flory, Brie Loskota, and Donald Miller, Center for Religion and Civic Culture, USC "Forging A New Moral and Political Agenda: The Civic Role of Religion in Los Angeles, 1992-2010," 2011

21 I have adapted this distinction between operative and normative systems from P. F. Diehl, C. Ku D. Zanora "The Dynamics of International Law: The Interaction of Normative and Operating Systems" International Organization, 57, Winter, 2003, pps. 43-75. I am grateful to Joel Rosenthal for pointing out this reference.

20 Pastor, Manuel. Marcelle, Enrico A. (2013) "What's at Stake for the State: Undocumented Californians, Immigration Reform and our Future Together," Center for the Study of Immigration Integration, University of Southern California, May. More Information: http://csii.usc.edu/undocumentedCA.html

23 Roger Waldinger (1999). "Not the Promised City: Los Angeles and Its Immigrants," Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 68, No. 2, May, pp 253-272; Philip J. Ethington (2000) "Into the Labyrinth of Los Angeles Historiography: From Global Comparisons to Local Knowledge," Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge, A Multimedia Essay http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/history/historylab/LAPUHK/Text/Labyrinth_Historiography.htm

24 See supra note 12 Waldinger; see also Greg Hise (2004). "Border City: Race and Social Distance in Los Angeles," American Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 3, Sep., pp. 545-558. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068233.

25 Los Angeles 2020: Time for Truth, 2013; Scott Kurashige (2008). "Crenshaw and the Rise of Multiethnic Los Angeles," Afro-Hispanic Review, Vol. 27, No. 1, spring, pp 41-58

26 Raphael J. Sonenshein, (1989). "The Dynamics of Biracial Coalitions: Crossover Politics in Los Angeles," The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 2, June, pp 333-353.

27 Jennifer Bradley et al The Metropolitan Revolution (Brookings, 2013)

28 Richardson and Gordon "Globalization in LA"

29 LA 2020: Time for Truth, 2013

30 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels The Communist Manifesto (1847)