To mark Carnegie Council's Centennial, Michael Ignatieff and team set out to discover what moral values people hold in common across nations. What he found was that while universal human rights may be the language of states and liberal elites, what resonate with most people are "ordinary virtues" practiced on a person-to-person basis, such as tolerance and forgiveness. He concludes that liberals most focus on strengthening these ordinary virtues.

VARTAN GREGORIAN: It is my great honor to welcome to the Carnegie Corporation of New York Michael Ignatieff, the president of Central European University (CEU), the former leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, and the former director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard. He is a man of conviction, honesty, intellectual integrity, as well as a great leader and educator—and none of these are tax-deductible statements.

I would also like to welcome trustees who are here from Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, the Corporation's sister institution and co-host of tonight's event, as well as Leon Botstein, president of Bard College and chairman of Central European University.

In addition, it is my great pleasure to welcome—a prepared remark, but I am going to do it. I was told George Soros will be here. I might as well use in his absence what I was going to say about him—the founder of Central European University, among many other institutions. When I was a student at Stanford University, I read The Open Society and its Enemies by Karl Popper. I never thought one day I would meet an individual who would put Popper's ideas into practice. However, George Soros is that man. He has never shied away from taking on the opponents to an open society, including in his native Hungary as well as elsewhere in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Hungary, of course, is home to the Central European University. The recent charges against the institution, which I am sure most everyone here is aware of, are ridiculous and unconvincing, and I thought maybe they belong to Transylvania. [laughter] As a former trustee of Central European University, I can say that I have met many professors, students, and administrators from the institution, individuals hailing from the United States, Europe, as well as many non-Western countries, as well as those who through their work strive to serve Hungary, Central Europe, Eurasia, and the world.

I thought at one time that the Central European University would be central Ural-Altaic peoples and claim that it was bringing for the first time individuals, professors, and students from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, all the Central Asian countries—but I guess the president of the Republic of Hungary does not realize that that mission was being implemented by the Central European University, otherwise there would have been no problem of internationalizing that university, the first American major university in Central Europe.

This being said, the Central European University we are aware, of course, here is great. But tonight we are here to celebrate the man, the leader, and the author of the book The Ordinary Virtues: Moral Order in a Divided World. I don't know about you, but more than ever we need to hear moral voices and standards and others, and I don't have to say why. If ever we needed such voices, today is one of them.

With that, it is my pleasure to hand the podium over to my friend and colleague, Joel Rosenthal, president of Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. Thank you. Welcome.

JOEL ROSENTHAL: On behalf of the chairman of our Council, Steve Hibbard, and several of our trustees present here this evening—Barbara Crossette, Susan King, Amir Pasic—thank you, Vartan.

It is easy to thank you for your generous remarks and for hosting this program. It is harder to find the words for all of the other things you have done for our Council, things big and small, seen and unseen, to support our Council's mission of making ethics matter. We are a different and vastly more effective organization thanks to you, Vartan. We continue to draw inspiration from you and your staff here at the Corporation, and from our Carnegie brothers and sisters around the world. I am grateful for this opportunity to thank you publicly for all of this.

Tonight is a noteworthy moment in Carnegie history. It is one in the series of occasions marking 100 years of Carnegie philanthropy. While this event and the publication of Michael's book mark the formal end of our Council's Centennial celebration, it is really the beginning of the next 100 years, which we begin with great enthusiasm and renewed resolve.

When Michael agreed to become our Centennial Chair, he set an ambitious course. He said we should explore new territory, we should get out of the seminar room, get out of New York, and into the heart of ethical debates around the world. Now, clearing new ground in ethics at the global scale is a monumental task, but this is exactly what Michael has done in his new book. This is exciting in itself, yet for us what is also exciting are the new areas for research and education that this work suggests.

Much of this new direction is suggested in an excellent article by Scott Malcomson in the Carnegie Reporter magazine. I encourage you to read it, along with Vartan's essay "Against Fragmentation: The Case for Intellectual Wandering." Read both of these articles and you will see what I mean.

For those of you following our Council's work, in the coming months and years you will see new streams of sponsored research along these lines, more opportunities for dialogue and exchange, and more multimedia efforts targeted at schools and the attentive public around the world. Our goal is to show the world why and how ethics matter.

I have had the opportunity to introduce Michael as our Centennial Chairman on several occasions—in Edinburgh, Sarajevo, Oxford, and here in New York. It always comes back to the same thing. As Vartan said, in addition to his comprehensive and deep understanding of history, philosophy, and politics, Michael is engaged in the issues of the day. He is not a passive observer; he is a participant.

It is not accidental that Michael is president and rector of Central European University at this moment in time. Michael is not only a scholar, teacher, and writer who has devoted his life to the values embodied by CEU, he has always been a defender of those values. Under Michael's leadership, and with the support of George Soros, the founder of CEU, and Leon Botstein, the chair of the CEU board, CEU is a beacon of free thought and expression in a world threatened by increasing authoritarianism. This leadership is exhibited in the CEU curriculum, of course, but also by CEU's role in the community.

The recent collaboration between CEU and Bard College's Center for Civic Engagement is a path-breaking example of how colleges and universities can do real and permanent good outside of the so-called "ivory tower." I know Jonathan Becker from Bard is here this evening, and I would like to acknowledge him for his leadership in these efforts.

Before giving the floor to Michael, I would just like to offer my personal thanks to him for the terrific effort that he put into this project and for the inspiring results it produced. As you will see, this project was multi-year. It required enormous time and energy, lots of travel, and much time away.

Thanks are also due to two others whose support was absolutely vital to this effort. First, a heartfelt thank-you to Devin Stewart. Devin, from Carnegie staff, accompanied Michael on his research trips and helped to organize things on the ground—and, trust me, these things are always harder than they look.

I would also like to give an equally heartfelt thank-you to Zsuzsanna Zsohar, who has been supportive at every turn, a great advocate for this work—and, as you are going to see in Michael's talk, it has really been a great team effort.

It is now my pleasure to give the floor to Michael Ignatieff, who will discuss his new book, The Ordinary Virtues: Moral Order in a Divided World, published by Harvard University Press.

Thank you.

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: This is one of these rooms where I could start thanking and acknowledging people and we'd be here until about 9:00. I look out at friends, colleagues, mentors, people who have helped me narrowly to avoid disaster at various moments in my life, people who have inspired me. I will try and keep it short. I have some things to tell you.

I think the whole room has deep affection for Vartan Gregorian. There is something joyous about this guy. There is something, as we say, "life-enhancing" about him. So thanks for being joyous and life-enhancing.

I want to thank Joel Rosenthal, who didn't laugh me out of the office when he asked me for advice about how to celebrate the centennial of this visionary man's gift [Andrew Carnegie], the creation of what became the Carnegie Council, and I said, "You've got to get out of New York." I was kind of just playing around. And look what happened—three years later and many thousands of miles, we created and completed a rather extraordinary project, which I want to talk to you about.

Joel has already mentioned one figure who I really want to emphasize again, and that is Devin Stewart. Devin accompanied me every mile of the journey, and I just want to publicly acknowledge an incredible act of collegiality and friendship in the shaping of the project. So, thank you Devin. Thank you, Joel.

Thank you all for coming. Thank you to everybody at CEU. We've got Open Society Foundations global board members, we've got trustees of the university. This is a power-packed room, folks.

I hope we also have time for a good discussion. I don't want to prevent you from asking searching questions because a couple of things I say will not be bland and vanilla; some things I say are going to be possibly hard for some of you to swallow. But that's my job, so let's get going.

Let me just tell you a tiny bit about the Centennial project.

To commemorate this man's visionary foundation of the Council in 1914, the Council authorized us to go basically around the world—to the United States, to South Central Los Angeles, to Queens, New York; to Fukushima, Japan, to Bosnia, to Brazil, to South Africa, to Myanmar—to study what I came to call the "moral operating systems" of divided societies, and I'll explain what I mean by "moral operating systems in a minute."

How did we do it? We had two kinds of things. We had global ethical dialogues in which, because the council has Global Ethics Fellows around the world, we asked them to convene smart people in Rio, in Pretoria, in wherever, and have discussions with them about the pressing ethical issues at the center of their minds. Example: You go to Rio and you want to talk about corruption and public trust, and I'll take you through that. So we had global ethical dialogues with experts.

But, very, soon both Devin and I began to feel we were still in the seminar room. One of the features of going to the ends of the world is that you discover that everybody has just completed their degree at Columbia, so you have a sense that you can never escape a certain kind of conversation. Very rapidly, we wanted to step out of the seminar room, and I'll show you some examples of some of the very strange, fascinating places we ended up. So we had global ethical dialogues with elite groups.

We had site visits—and you'll see some of the site visits that we went to.

The result is a book available at all your good bookstores—there are a whole bunch of copies behind—published by Harvard University Press. If there is anybody from Harvard University Press, thank you very much for sticking with this project.

Let me try to explain what I mean by the "ordinary virtues" very briefly.

By "ordinary virtues" I simply mean the virtues of ordinary life. And by "ordinary people," I mean you, I don't mean some other group of people who are not in this room. I mean the ordinary reasoning, the ordinary display of moral behavior, that all of us display.

The virtues that I am looking at were, in a sense, the positive ones—pity, compassion, tolerance, friendliness, forgiveness. I am interested in those virtues that make for moral order, that keep the show on the road, the microscopic interchanges between human beings that make for a moral world as opposed to a jungle. Everywhere, in every social setting, people are knitting together what I would call the "moral operating system" of their particular world. By "operating system"—it's a metaphor to computers and stuff—all I mean by that is when you turn the thing on, you forget about it. It is a sense of the tacit, the unstated, the implicit. That is what I am trying to capture by the idea of a moral operating system.

But these virtues—and here we set up the question that I was interested in—are very local. They are the virtues of a community, they are the virtues of small settings. The question that we went around the world looking at was the relationship between the universal values—let me pick one, human rights—and these local virtues.

It is commonly assumed that the ordinary virtues are the source of human rights universalism, that it is some basic intuition we have about human beings that allows and structures and undergirds the idea of universal values, like human rights. I was struck, on the other hand, by something very different, which is that the ordinary virtues and universal values are in much more tension than we like to admit, and a lot of the inquiry that we went through over three years was looking at that tension in action. I will give you some examples of what I mean.

The kind of questions that organized this study were: "What keeps a liberal democracy together?" We have an institutional bias when we think about open societies or liberal democracies. We put an emphasis on rule of law, we put an emphasis on the Madisonian machinery that keeps this thing together, and we don't focus on the micro-sociology of virtuous behavior and the operating systems reproduced in society that make these societies cohere. I was interested in what happens when these operating systems are put under pressure; what happens in fragmented, in divided societies; what happens when the moral operating systems and the local virtues are put under pressure?

I was also interested, since these are private virtues and local virtues, in what happens when political discourse starts to work on them. What happens when a Trump, a Viktor Orban, goes to work on people's emotional feelings? How does that impact the operation of the ordinary virtues?

And then, this question that I have already suggested: How do we handle the conflict between local virtues and universal values; the universal values of human rights, duties to refugees and strangers, versus the local virtues, which are pride in your nation, pride in your community, preference for us versus preference for them?

Let me give you, very briefly, a sense of where we went. That is kind of an intellectual menu, but let me tell you where we went so you see where we traveled.

I will tell you a funny story. We first went to Rio in June 2013.

We had one of those global ethical dialogues with experts. It was kind of hilarious in retrospect, because we got them around the table—I don't mean to satirize them, they are very wise and able people—and we talked about corruption. They all said, "Well, there is a culture of corruption in Brazil, but there's nothing you can do about it, because basically the Brazilian public accepts that everybody is on the take. So the political culture of corruption is undergirded by a public culture of acceptance." That was fine. We listened to that.

Then I began to look out the window, and out the window, first, there were about 10 people carrying Brazilian flags, then there were a hundred, and then there were a thousand, and then there were 10,000 people in the street. I said, "What's going on, folks? We'd better get out there and take a look."

That was the beginning of the million-person demonstrations against corruption in Brazil. So the experts told you one thing and the people were telling you another.

I am a dyed-in-the-wool, convinced, and proud intellectual. I will not traffic in anti-intellectual populism of any kind. But, let's be frank: Sometimes the experts get these things wrong. Here was a dramatic example. We followed those demonstrations for three or four days and began to get a sense of the visceral fury of the Brazilian public about the corruption issue that the experts had not seen. It was visceral fury that also ended in very strong amounts of violence that smashed cash machines.

We then looked at the relationship between corruption and moral order. When you ask yourself, "Why are these people in the street?"—corruption, I think, affected Brazilian citizens as humiliation. The connection between corruption and humiliation is not well understood. Over and over and over, people said to me, "How stupid do they think we are? They are stealing, and they think we don't care." That is what I mean by corruption as humiliation.

Let me also show you another place we went, because we went away from the experts to a wonderful place called Favela Santa Marta.

Favela Santa Marta is a thriving, extremely poor community perched on the hillside of Rio de Janeiro. It has been beset by drug gangs, it has been beset by violence, but it has been the source of a very important experiment in policing in which the police basically reconquered the favela over a period of a couple of years and reestablished order.

Why was this interesting to us? Because it allowed us to see the relationship between the rule of law and the moral operating systems of poor societies. It became very clear looking in Santa Marta that if you can have minimally fair policing—i.e., policing where they don't shoot you because of your race, and they kind of try to arrest somebody when a crime is committed, minimal standards of rule of law—moral order can rebuild in a place like the favela, and we saw it being rebuilt all around us.

What am I looking at? I am looking at mothers leaving their kids with a neighbor. I am looking at people looking after their elderly relatives. I am looking at churches beginning to function, the molecular creation order in extremely poor communities, but absolutely dependent on the rule of law, dependent on the police, and we saw that going on.

The same theme occurred in South Central L.A. The very ferocious-looking guy in black glasses is actually pretty ferocious, an ex-gang leader in South Central L.A., who, having done about 15 years in the tank in various prisons, decided to turn his life around and begin to turn the next generation away from crime.

One of the ways to think about him in terms of the moral operating system of South Central L.A. is that he is writing code for the moral operating system of that community, trying to get young people to turn their lives around. He is a moral agent in these settings. We talked to him again about the tremendous importance of having rule-of-law institutions that support and sustain his kind of efforts.

In a way, Los Angeles is a place in which you see the repair of a broken moral operating system following the Los Angeles riots of 1992. The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) cleans up its act, the community gets to work, and you see a moral operating system being put back into place.

We also went to Jackson Heights, Queens, again to look at another feature of the moral operating systems of these societies.

How is it that Jackson Heights, Queens, is the most diverse census tract in the United States? It is a bus station. It has 180-190 ethnic groups living side by side in relative peace and harmony. It seems to me actually mysterious, wonderful, and extremely positive that this community coheres. What is the moral operating system that allows people who do not share the same language, the same religion, the same politics, the same views, to live side by side? How does this diversity work as a moral system? This was the question we asked in Jackson Heights, Queens.

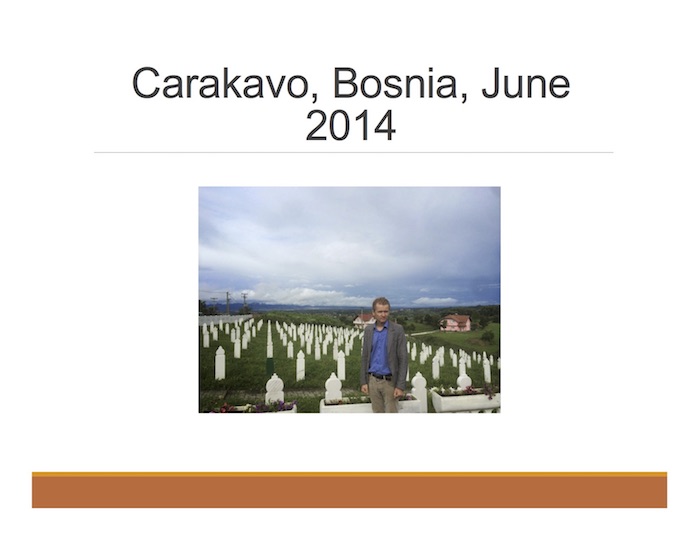

We then went to Bosnia because we wanted to look—this is a man, a Bosniak, standing in front of a Muslim burial ground that contains 276 bodies of the Muslims who were massacred in a single day in his village. He buried them all and put the monuments up himself.

Here is the question: He lives beside Serbs, he lives beside the perpetrators 25 years later. How is it that forgiveness works in these micro-settings? How is it that he manages to live among perpetrators and recreate a form of moral order between victims and perpetrators? He said something fascinating to me. He said, "I've learned not to generalize. That is, there is no such thing as a guilty Serb in general. There are some Serbs I can't stand, I can't forgive, I can't forget. But he, he was okay."

The logic or ordinary virtue is extreme individualization: I don't generalize. I take people one at a time. I take people as they come. I began to learn the moral wisdom of this studied refusal to generalize as being a key to the reproduction of moral order in these conflicted settings.

Here is another place. We go to South Africa.

This is a community called ZamaZama outside of Pretoria, South Africa, where you are looking at another thing: How do you produce moral order in the total absence of the state?

In ZamaZama there are no cops, there is no welfare system, there is no sanitation, there is no water. The government of South Africa might as well be on Mars, and yet it is half an hour from the capital of the country. How is it that communities entirely abandoned by the liberal state—the state that wrote the world's best liberal constitution, the 1994 constitution—how does moral order cohere in a society that has been abandoned by the Mandela state, the African National Congress (ANC) state?

Again, we saw the same molecular, complex process in which people create forms of moral order, because these folks know one thing: it is very bad to be poor, but it is much worse to be in a place torn apart by violence. What was interesting to watch here is this is a naturally Hobbesian situation that did not turn Hobbesian. This is a moral operating system working in extremis.

I am going to get to the end of my tour, but I want to take you to another. Each of these features are chapters in the book.

You will see me not smiling. I am not happy. I am not happy because I am talking to an extremist Buddhist monk, who makes a very good living preaching hatred toward Islam, Muslims, and the Rohingya.

That raised another issue, which is, it seems to me, central to understanding moral order, which is the role of political discourse in confiscating emotion.

Think about this. He is a man who gets up in small communities—for example, Mandalay in Myanmar, a beautiful place—and he spreads a message of hatred toward Muslims. There are a lot of Muslims in Mandalay, as it happens. They have been there for centuries. They are commercial traders. They live in harmony with their Buddhist-majority neighbors. He spreads a kind of poison which confiscates the possibility of tolerance, confiscates the possibility of saying, "Well, you know, some Muslims are okay folks." That individual, particularized moral reflex, these political discourses confiscate that, remove the space in which someone can say, "Well, actually that Muslim guy is my neighbor."

That is an example—of which there are plenty of examples around the world—in which political discourse has a huge role in shaping the possibilities of a moral operating system. It can confiscate the expression of virtue.

It can also empower the expression of virtue. There are political cultures, for example, which make it fashionable, acceptable, and a nice thing to be generous toward refugees, to be generous toward strangers. As you know, Canada is a perfect country, it is a faultless place, it is paradise on Earth politically, but that would be an example of a country in which a political culture empowers a moral emotion, in this case, generosity toward strangers.

Finally, I wanted to look at moral order in situations of utter devastation: a force-nine tsunami, a devastating nuclear release, a community thrown back to a—it is as if the society is destroyed in one moment, in one 30-40 minute period: 30,000 people drown, communities are devastated through Northeastern Japan. And my question was, how does moral order get reestablished in situations of devastation and catastrophe?

One of the ordinary virtues I am most interested in—and we all should be interested in—is resilience. What is resilience? How do people show resilience in the face of catastrophe? The place in the world that can teach you most about resilience are the small devastated towns of the Fukushima Prefecture, where Devin and I spent a lot of time together.

There you saw another thing about the moral operating systems of these societies: They are deeply historical. If you asked a guy who just lost everything why he had the faith and confidence to rebuild, they said one of two things. They said, "My family has been here for 400 years. Do you think a tsunami is going to get us out of there?" A recourse to historical strength to get you through.

Second, a recourse to things that we usually dismiss as a kind of TV joke, the samurai tradition. We may think a samurai is just something you see on the TV, but for these folks this was real. Men thought of themselves as samurai. It is very gender-coded, of course, but it gave them the resilience to survive the unimaginable and unthinkable.

There we are. That was the tour. These are the issues we raised.

I want to get now to some conclusions and take you into some controversial terrain. What do you learn when you go to six places like this and you look at, as you can see, very different themes? But are there overarching themes that come together?

One of the things that I do not think we think about enough is the enormous moral impact of living in a post-imperial world, a world in which the empires have been dismantled. Somebody who looks like me and talks like me, especially if I was British, had I been an adult in 1945, a tacit, unstated assumption of my moral universe was that I was born to rule. Ask a Frenchman the same, ask a Dutch person the same. The sense of unavowed but deep moral superiority that came with imperial power—we need to understand decolonization and the dismantling of empire as having an enormous moral impact in two ways.

That is, it delegitimizes the master races. This is both an international phenomenon, but it is also a domestic phenomenon. You cannot separate the American civil rights revolution from the international decolonization revolution. They are both going on at the same time, they are both powered by the same emotions, and they are both an attempt to create a post-imperial moral universe based upon the idea of the moral equality of all individuals.

This global norm of an equality of voice has, as I'm trying to say in the slide, three dimensions.

There is the self-determination revolution.

There is the democratic revolution—Eastern Europe and the world have adopted the democratic norm. Do not forget that, even in China and Russia, the norm is the ideal of popular sovereignty as the basis of political legitimacy. We do not see how far this idea of moral equality has run.

The rights revolution has empowered this as a language of individual empowerment, and that includes the civil rights revolution, the feminist revolution, the revolution in gay equality.

We just are in a different moral universe than we were in 1945. How does this translate when you are out on the road? It translates into something that it takes you a while to realize.

You sit down with the poorest people, and they all look you in the eye. Nobody lowers their gaze. Nobody thinks it is odd that someone has come from far away to ask them moral questions about the meaning of their lives. They take it for granted that they have something they want to say, and they take it for granted that I am there to hear and listen. In 1945 I just do not think that the dialogues that we had, the site visits that we had, would have been conceivable. The conversation would not have occurred. There would have been silence on the other side.

That seems to me a revolutionary aspect of the modern world, which, in the middle of all the bad news we have, is a very important thing we need to think about. And its implications are ambiguous. The more the moral claim of equality makes its way in the world, the more impatient everybody is with the deep inequalities that remain. There is a dialectic of insatiability here.

I am not claiming we are all equal. I am not claiming the inequalities are less flagrant than before; I am saying they may be more flagrant than before. But the starting assumption of everybody is "I matter." You go to the poorest communities, they say, "They can't treat me like garbage." This is a revolution in moral feeling we need to understand.

But it comes with a complication that I think we need to think about, which is that you would think that a global norm of equality—undergirded, for example, and expressed by the language of human rights—would produce more human solidarity across groups. Almost the central paradox of our work was to feel, on the one hand, people are saying, "You can't treat me like garbage. I'm as good as anybody else. I'm equal." On the other hand, the frame of reference for their moral lives was intensely local and has gotten even more local. Moral globalization has not produced more moral solidarity across ethnic groups, across races, across religions.

So you have the paradox of equality without solidarity.

That we saw everywhere. If you asked people in ZamaZama, "Who do you care about?" they care about ZamaZama. You ask in the Favela Santa Marta, "Who do you care about?" they say, "I matter, I can't be treated like a piece of garbage," but their solidarity is extremely tightly bounded by the favela, not beyond it. This is a paradox of our time that needs to be thought about, and it leads to some very difficult questions about human rights universalism.

I have taught human rights for a decade. I'm signed up. But in a proper doctrine of human rights universalism, there is no other, there is only us. The otherness is constructed, it is not real, and otherness is morally irrelevant in determining moral duties. So the duties of common humanity trump any local allegiance and local belief, and that means that asylum and protection claims for strangers trump, when it comes to the claims and rights of citizens.

The point I am trying to get to here is that the ordinary virtues perspective sees the world in very, very different ways, and we have to face up to that. For all the people that I talked to, the primary distinction is self/other, us/them, citizen/stranger. I am not essentializing that, I am just saying that is what I saw.

The idea of a common humanity comes very, very late to the story. The primary duties are local. This means that race, religion, gender, nationality—all the markers of difference that human rights universalism regards as constructed, something that we can get beyond and get over—does not sound right from the ordinary virtues perspective.

Difference is primary. Common humanity is conditional, by which I mean you discover that someone who is very different from you is actually a member of the same human race. You begin to negotiate commonality. You do not start from commonality. You establish it as you establish real relations. You meet a Muslim, you meet a Jew, you meet a black person, you meet a white person, you meet a gay person, and from that encounter with difference you begin to construct a narrative of commonality, but it is very fragile, very vulnerable, and easily broken by the primary claims of the ordinary virtues.

So if you look at—and here I want to make a contrast between gifts and rights.

If you go anywhere that is multicultural and diverse or you go to any frontier between a citizen and a stranger, this is a transaction, it seems to me, in which a citizen says, "If I'm going to tolerate somebody, it's a gift." Tolerance is a gift, it is not an obligation. Tolerance is conditional. Tolerance is something I give to someone. It is not an obligation that follows from their rights. This illuminates the contrast between a human rights perspective and an ordinary virtues perspective.

If a stranger comes to the gate and says, "I have a right to be admitted, I have a right to your toleration, I have a right to your compassion, I have a right to your generosity," a citizen thinks: Wait a minute. You don't understand this transaction. This is a gift transaction, not a rights transaction. I do not think human rights—and I am a human rights guy—have thought enough about the radical contrast between the language of the gift and the language of rights. That is one of the things that is highlighted by the contrast between the ordinary virtues perspective and the human rights perspective.

To get to a burning contemporary issue, when you look at the dialogue on refugee and asylum rights in Europe, you have people who believe in asylum policies in the 1951 Convention, in the obligations of states, talking a rights language which simply hits a wall of incomprehension from citizens, because they start from a different premise: There are citizens and there are strangers. Strangers come to your door, and citizens decide who gets the gift.

Asylum is a gift. It is not a right. Shelter is a gift. It is not a right. The transaction is a transaction of compassion and generosity, not the acknowledgment of reciprocal obligation.

I am trying to describe the political sociology we are dealing with in Europe and many other places. If you ask why the Trump attack on migration and refugee policy strikes a chord, it is because he is saying, "We are the gift givers. We'll decide. It is discretionary. Citizens come first. Strangers come second." It is a discourse right across the developed world.

How do you understand the German election last night? The language of the gift is battling with the language of rights—and, frankly, the language of the gift is winning. I am not saying it to praise the language of the gift, I am trying to describe the politics of what we are looking at.

I do not want to essentialize the ordinary virtues.

I do not want to say they are incorrigible. I want to say, in fact, something very different, which is that this language of generosity, compassion, and mercy, which is crucial to sustain if we are to have asylum and refugee policies that are something better than barbarism, we want to sustain those languages.

But we are faced with a battle in which populist rhetoric—Viktor Orban would be one example; Alternative für Deutschland is another, and I can go around the board; Donald Trump is another—in which we have to understand that what is going on is that this is political discourse that confiscates the virtues, that simply says, "It is disreputable and a betrayal of your country to show generosity and compassion to a stranger."

This language is reworking the political emotions upon which a migration and refugee policy depends. Liberals like me who want a generous refugee policy—"Hey, it's my trade union. My father and my grandfather were refugees, right? What else can I think here?"—have watched the collapse of any political support for refugee and migration policies simply because we do not understand the deep degree to which our fellow citizens regard the language we use, the language of the right, as mistaking what is actually going on. It is a gift transaction.

So what do we do about that? How do we do this?

I think we have to start changing the political language we are using. That means we have to, in my view, strengthen the ordinary virtues.

The ordinary virtues here are the language of compassion, generosity, and mercy. But you cannot do it unless you understand the ways in which citizens see a primary distinction between a citizen and a stranger and view the acceptance of a stranger into a society as a contract in which, "We say yes to you on condition that you say yes to us." In a gift transaction, you are grateful for the gift. You say, "Thank you."

This does not fit at all with the language of human rights, where we simply acknowledge your right and accept an obligation. In the integration compact that ordinary virtue understands, we will say yes to you if you say yes to us.

Then we want to do something else, which is fight back against a political language which is confiscating the language of generosity, compassion, and mercy with a language that tries to get to the inside of ordinary virtue, which is: take people as they come; take people one at a time; refuse false aggregation; refuse Muslims, refuse Jews, refuse blacks, refuse whites, refuse gays; refuse all of it; refuse those kinds of universalizing languages wherever we can, to focus on the individual in front of us and reconnect ordinary virtue to individuals, empower the ordinary virtues with a language of generosity.

Again, as you know, Canada is a perfect country. But if you ask why it is that the Canadian refugee policy has been successful, it is because it has not used the language of rights. It has actually said, "We are a generous country, we are a compassionate country. This is about compassion, this is about us."

I am not saying I like all this language, but I am saying you have to understand the moral resonance of language like this if we are going to turn this around.

Let me come to a conclusion.

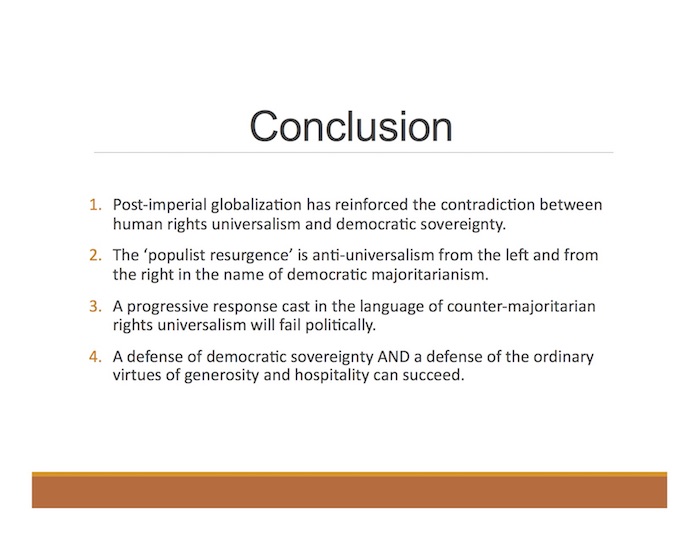

I have said, on the one hand, that this journey we took was kind of a study in post-imperial moral culture. It was a study of the moral operating systems of a 21st-century world, and it is a post-imperial moral world. It is a world based on basic equality of voice but not enhanced or deepened human solidarity. That is the paradox we saw first.

There is an increasing conflict between human rights universalism and the political language that has caught the ordinary virtues, which is the language of democratic sovereignty, the language that privileges the citizen over the stranger, the language that says, "We must decide who gets the gift."

That is the enormous appeal of these nationalist languages, because at the bottom of this is not viscerally rational nationalism but a powerful appeal to democratic sovereignty: "If we are going to give gifts, we, the people, will decide who gets the gift." That is the logic here. We need to understand this language—not approve it, not endorse it, but understand what we are dealing with.

The populist resurgence is deeply anti-universalist. We need to fight back with an insistence on the crucial importance of counter-majoritarian rights talk in domestic constitutions. What has been the most effective opposition to Trump? It has been the lawsuits in the American constitutional process.

Please do not hear me saying I want to jettison rights talk or counter-majoritarian protections. I am just saying that the political battle will not be won with rights talk alone. I am saying a progressive response cast in the language of counter-majoritarian rights I think will lose, but a progressive response cast in the language of democratic sovereignty and a defense of the ordinary virtues of generosity, compassion, and mercy I think can turn the tide.

Thank you for your attention. Sorry to go on a little longer than I intended.

I am happy to take questions. Since I have said some things with which you may disagree, I hope you will be as disobliging as possible.

QuestionsQUESTION: Thank you. Do any parties that you have run for prime minister on believe in these [inaudible]?

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: I ran for office in a country that—again, so much of this depends on the collective identity—a country that has self-described itself as an "immigrant nation," a country that has self-described itself as a "generous country," often in invidious and self-congratulatory ways—i.e., "We are more generous than those Yankees to the south." I do not want to endorse all this. I do not want to miss irony about this. Some self-descriptions the country has are as phony as anybody else's, and Canada is no exception.

But the politics that I was part of was able to tap into a kind of reservoir here that was very easy to draw on. My concern is that the reservoir is drying up. It is drying up everywhere. It may have dried up in Germany last night—I don't know.

I am astonished at what is happening in the United States, because you have one of the most generous and far-sighted refugee policies in the world, you have led the world in this, and yet, somehow, there is a kind of way in which that generosity has been confiscated. It is not that it has disappeared, it is not that it is not there, it has been confiscated. You look like a sap if you say, "We ought to take some Syrian refugees." You can look like an unpatriotic American if you say, "We ought to open our doors to strangers." That move is something, it seems to me, we have to understand and then do something about.

QUESTION: Michael, you make a really persuasive case for the importance of the post-imperial order. I am not sure you are taking it far enough. Where I think I disagree with you is I do not have a problem about talking about the relationship between citizens and non-citizens in the terms of the ordinary virtues that you are speaking about, but within the nation-state I think one of the most important things about the post-imperial order is exactly the recreation of nation-states.

Within India, for instance, I will not, as a woman, speak or demand anything in the language of the ordinary virtue. I will only demand it as a citizen. That distinction, therefore—

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: And why is that, because you have been actively disempowered, or you think it is not the right thing to do, or what?

QUESTIONER: No. Because the most important thing of the post-imperial order is that I am a citizen, and because I am a citizen I will not ask for the fulfillment of rights in any language but that.

But we are very busy throwing the Rohingya out of India, and there is very little counter-response to that. It is almost like, "Well, you know, they're not us."

So I can see this, but I think there is a distinction that is really important.

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: Yes, and there is no question that the language of citizenship has been the key moral language of a post-imperial order. What self-determination has given people is the sense that they can speak as citizens. That I absolutely see.

But I am saying your Rohingya example is good. That language is not empowering you and does not create constituencies to defend vulnerable populations.

QUESTION: Thank you. I want to challenge you a bit on what I understand is your analysis that the individual-to-individual, the ordinary virtues, you can build a political order on them through democratic sovereignty. Indeed, in terms of human rights, it is true that the notion that we would have the same fellow feelings for people who are a thousand miles away from us as from people who are a hundred miles away is an abstraction, it is not true, and it does not correspond to the reality of humanity.

But I wonder—of course, I am a Frenchman, so you always bring things back to liberté, égalité, fraternité — I wonder whether, after the end of the Cold War, there has not been a bit too much of a focus—and I wonder whether you are a prisoner of that—on individual agency, and that in reality human communities, they also believe in collective agency, and where that follows on what you said about India and about the response to empires.

Was decolonization the empowerment of individuals or the empowerment of nations? And then, if it is the empowerment of nations, of collective groups, then we have all the questions of "What is a community today?" in a world that is torn apart by transnational identities, by a variety of forces, that have destroyed the self-evidence of a human community, and so democratic sovereignty begs the question of "What is the framework in which that democracy works?"

So my challenge to you would be: yes, you cannot ignore ordinary virtues, and the pretense of human rights that you can build a sort of universal community does not correspond to the human experience, but nor is human experience based on the ignorance of that collective dimension between the universal and the individual.

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: That is a strong point. My individualism point was actually more narrow than I think you are taking it.

I was just enormously impressed that when I saw a struggle going on at the ground level, which I think we all experience, between the constant production of collective images of the other—the Muslim, the Jew, the gay, the back, the white, whatever—the constant reproduction of those discourses, some of them are reflected in those communities themselves—and we misuse "community" all the time—what I see is an estimable moral struggle when I see it engaged for people to say, "I am not going to buy these collective identities. I am going to look at the person in front of me."

My mother said a wise thing to me—and you have to listen to your mother, right? She said her idea of heaven was a place where all dislike was purely individual. It is a brilliant remark, actually. It is you. It is not that you are a Frenchman or a man or a person of a certain age; it's you that I don't like, or like a lot. Do you know what I mean?

That struggle—that is the point I was making. There is something very good to be said about moral individualism at this point, and that was the only point I was trying to make.

The thing I would go on to say is that there is a lot of loose talk about globalization, but everything I saw was reinforcing the enormous attachment of local community, national identities, racial identities, linguistic identities. I do not know how we bought an idea that we were all heading in one direction and that we were all going to be morally globalized as well as economically globalized. Nothing of the kind has happened. All the local, national rooted identities are stronger than they were, in my view, 25 years ago. They are all changing, but they are not disappearing anytime soon, which to me seems like actually a good thing.

QUESTION: Michael, I think you showed the picture of the Buddhist monk, and that raises the issue for me: you don't deal with diasporas. I lived through Soviet Jewry coming. They did not feel, many New Yorkers and Chicagoans and others, that their fellow Jews, no matter what language they spoke, would not be welcome as an act of solidarity, the group solidarity, diaspora solidarity. The same thing about Lebanese in Michigan. The same thing with Iranians in Los Angeles. I do not know how that figures, if you look at the same thing—Irish, in terms of no matter where you are Irish, you are always part of the community you separated from.

I do not think you deal with that issue, and I do not know whether that has any validity or not, but I found that all the arguments you made disappear when a Jew or a Lebanese or an Iranian or others are going to rejoin their local community with generosity and right and opportunity coincide. Would you comment on that, please?

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: Yes. As someone whose father and grandmother grew up in a Russian community in Montreal, I know a little bit about diasporas. What you are saying is that is a form of transnational solidarity which is stubbornly enduring.

The only thing I would say about it is that, from a human rights purist point of view, it is always regarded as a certain kind of suspect partiality. That is to say, Jews looking after Jews, Liberians looking after Liberians, Russians looking after Russians, that is somehow regarded as a slightly imperfect form of solidarity. My view is, "Hell, I'll take anything I can get here," and diaspora solidarity seems to me extremely important.

Now, let's be honest, there is an extremely negative side to it as well. In the Yugoslav catastrophe, some of the most extreme, intransigent, inciting forces driving the dynamic in Yugoslavia off the cliff were diaspora communities urging their people on.

So let's emphasize the positive solidarity, which you are emphasizing, but let's also not forget some of the negative sides as well.

QUESTION: Good evening. Thank you. I am a CEU alumnus. I am very pleased to be today here and to listen to your presentation.

My question is related to neoliberalism and distribution of wealth. What role does the distribution of wealth play in constructing this image of "us versus them"? And if you identify also a class identity among a gender, race, and if people divide themselves also along class issues and socioeconomic issues, not just identity politics—if you can elaborate a bit on that?

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: I was struck in Favela Santa Marta, and also in ZamaZama, South Africa—yes, an identity of being poor, but that is not a class identity. They all wanted to get the hell out. It did not bring them together—"We're poor, but we're proud, and our identity is formed by that." It was a negative identity that they wanted to escape.

But let me turn your question around a little bit and refocus it—not because you did not ask it precisely, but I want to go in a slightly different direction. One of the really interesting moral questions that we do not look at is how extremely unequal societies, in terms of income distribution, class divisions of the kind that you are evoking, do not produce explosions, and how do they cohere, given that everybody knows the deck is kind of stacked in a way, and yet they reproduce over time.

And when is it that they actually explode? That is what makes Los Angeles so fascinating to me. When did Los Angeles blow up? It was not because some people are driving around in Maseratis and some people are in some old Ford Pinto. It was not because some people are working $12-an-hour jobs if they're lucky and other people are making $1,000 a second. The reason it blew up is that they beat a black guy up on camera, and the rupture of the moral order there, that is where it occurred, because the box says "the Fourteenth Amendment," that is what the box says, right? And they get told every day that is what is supposed to happen. Then you get whacked on the head with a nightstick because you are black, and badly beaten, and somebody videos it, and then the place really goes.

That, it seems to me, tells you something fundamental about the moral order of our societies. In other words, you can put up with a hell of a lot of social inequality, economic inequality, stacked decks, but if the cops start beating you up because of your race, all bets are off. It is a recurrent pattern—1965 in Watts, 1992 in L.A.—and it brought home to me, as an old paid-up liberal, that we do not think enough about decent policing as the core of a liberal order. But it redoubles the perplexity because we live in very unequal societies.

Everybody in this room is very privileged, and we are proud of our achievements and accomplishments, but we are aware that it is tough out there, but the show goes on. So my question is, why does the show go on, and what is the moment when the show does not go on anymore?

The observational sociology tells you to look at Los Angeles. That tells you a lot about that question.

QUESTION: I'm Sarwar Kashmeri from Norwich University. As I was reading your book—

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: Oh, my god. I think you are the first person who has actually read this book. That is amazing.

QUESTIONER: As I was reading it, former President Obama sent out a tweet that said—and I'm paraphrasing, but it is pretty close—that "No child is born hating anybody." It turned out to be, I think, the most widely read and quoted tweet.

I wonder, respective of what you have learned in your book, how do you account for the enormous popularity of that tweet?

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: I cede to no one in my admiration of the former president. I think the tweet was picked up because he said what people deeply want to believe, number one; and, number two, there is a lot of observational evidence to show that he is actually right, that we come out into the world not thinking difference is primary.

But I am saying we start thinking difference is primary pretty quickly, and that is a very, very complicated sociological, psychological, and historical story.

He put that tweet out at a moment when the beast had been let loose, and he wanted to remind us that it does not have to be that way, and we passionately want to believe that to be true.

QUESTION: I am a veteran. I think there were two times in my life when I really felt kind of a deep feeling of universal connection with everybody else. One of them was after the birth of my first son and one of them was when I came back from war. I think that part of the reason for that was the experience of comradeship in the Marine Corps in my case, and in the case of some other veterans, was capable of being universalized, making that leap from feeling very strongly about a group of other people and then feeling somewhat of the same feelings about everybody. I wish I could say it lasted. It has stuck with me, but it was a very strong feeling there for a while.

Why do some forms of limited solidarity stay insular—because, of course, some of my fellow veterans do not feel this way at all—and others seem to be capable of spreading themselves out in this way?

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: That is a really wonderful question, and it challenges my dichotomy between local attachments and universal ones. You are saying, in fact, that the little platoon—literally Burke's famous phrase, the "little platoon"—can generate universal feelings of attachment and commitment, because when the Marine Corps works and when you are under fire and under enormous pressure, you see human beings do things that are unforgettable, your life literally depends on it, and that can give you a feeling of expanded human possibility.

But you did say it did not last. You did say that it kind of fades. I do not think that means that it is false. I just think it just means life is very complicated, and the moments of exaltation that you have when you sacrifice together and struggle together and pull together in adversity, in combat, in those situations, are not ordinary life. They are very particular moments.

There is another side—and you would have much more experience about this than I would—but there are people who experience the exaltation of unity in a combat situation, and come back to ordinary life, and it is just so damned disappointing, it is so selfish, it is so divided, and they think, I saw what human beings can do when they pull together, and look at this, we are fussing and fighting.

But you are challenging my assumption that there is a kind of necessary antagonism between the local and the universal. All I can record is that I am listening hard to what you're saying and I need to think more about it. But it is a fascinating question.

QUESTION: I am so glad you are focusing on the ordinary virtues, this last slide, and defending generosity and hospitality.

Donald Trump told a story repeatedly during his campaign about the snake, about a woman who took in an ailing snake, an ailing creature. And then the snake bit her, and when she protested at this misuse of her generosity, the snake said, "You knew I was a snake all the time. Why did you take me in?" So it is not only you're being punished for being compassionate, but you are a dupe. And he has been engaging in this kind of emotional training for a long time.

How do we counter that? I am very concerned about that. How do we defend these—not only defend them but also kind of make a new offensive of compassion? Do we do it at the local level of community organizing, civic initiatives of education? Do we seed it into political candidates' messages? What do you think is the best way to counter this?

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: Well, if I had an adequate answer to that, we could all go home and be happy. It is extremely tough. But what Trump's story illustrates is this point that I am making about the confiscation of virtue, the ways in which, as you say, he turns the generous emotions, the ordinary virtues, into vices or into forms of foolish self-deception. And it highlights the extent to which all politics is like that, actually. It is important to grasp that. A liberal politics is fundamentally a politics of hopeful optimism that occasionally people can get to their better natures, as Lincoln famously said.

We think of politics in extremely instrumental terms—this program, that program, this fix to the health care system, that fix—but it is fundamentally a battle about who owns and defines social emotion, and we need to get in there. I am a spectacularly unsuccessful liberal politician, but I did learn that you could not win this battle by coming up with a really excellent six-point program. You had to have much more emotional intelligence than I had, you had to listen carefully to what people were saying to you, and you have to come back and say, "Are you seriously telling me that every stranger you ever met is a snake? Come on, Donald. Get serious here."

As an observation, it is factually untrue. Yes, trust is sometimes misplaced. Yes, sometimes you give a bed to a stranger for a night and wake up and discover your wallet is gone. So what else is new? How about the times when generosity is repaid with more generosity?

Let me give you another example, a more pointed one. Mr. Orban, the prime minister of Hungary, is engaged in a very passionate self-presentation as the defender of Christian values against the threat of Muslim immigration. Okay. You would never know from the way he talks about Christianity that there was ever a thing called the parable of the Good Samaritan. You would never know that Christianity is the language of mercy and compassion.

The language of Christianity has been confiscated in such a way that it is a marker of ethnic identity to the exclusion of everything else that Christianity ever stood for. And you have to get someone to stand up and say, "Are you seriously telling me this is the Christian faith? Let me quote some things to you, Mr. Orban," or whoever it is, and get into that battle.

QUESTION: Michael, I was puzzled by where you ended up about rights. You did seem to end up saying that rights talk is an obstacle in the face of the confiscation of ordinary values by populist rhetoric, although you did also say that rights were very effective in the courts.

So I am wondering, are you basically saying that in politics really rights discourse is something we should do less of, even abandon?

I ask this in the context of the argument of Sally Merry, the anthropologist, who writes about human rights, who makes an argument almost the opposite of what you are saying: namely, that the big problem is to render human rights vernacular, to take them down to the level of the village and make human rights intelligible, for example, when defending women who are being battered or whatever. That seems to me to run directly opposite of the way you seem to be arguing.

MICHAEL IGNATIEFF: On the vernacularization point, it is very well taken. Human rights has gone global by going local, that part of what Sally Merry is saying seems to me right. But all I am saying observationally, when I get into Favela Santa Marta and ZamaZama, I do not hear rights talk; I hear, "You can't treat me like garbage, I'm a somebody, my voice needs to be heard," but it will be a long time before anybody tells you "because I have a right to those things."

I am trying to do a kind of micro-sociology here observationally. I do not disagree with Sally's normative claim, that that is what we ought to be doing; we want to empower women in Santa Marta and ZamaZama to think, "I'm a rights bearer, I'm a woman, there are claims that I can make." But the ZamaZama case is particularly painful. South Africa has the best goddamned liberal constitution in the world, it has rights, and every liberal constitutionalist in every law school in the world teaches these kids that this is just the Maserati of rights constitutions. All I can say is when you get to ZamaZama it does not exist. I wish it were otherwise, I really do, but it just does not.

On the wider question—and this would be again a challenge to international human rights—what you see both in the British case in relation to Brexit and in relation to other things, and also in the American context, is that rights matter intensely. But it is not international human rights that matters. What matters is the constitutional rights tradition of the United States, and that matters hugely, because it has democratic legitimacy, it has the whole 200-year history behind it. So instantly, within hours of Trump's travel ban, you've got bright young lawyers going to the Fifth Circuit or the Seventh Circuit—I am not an American so I do not understand any of this stuff—getting injunctions to stop it. That is rights effectiveness of a—god bless them. But that is the stuff that is going to do it, frankly, and international human rights has been mostly a bystander.

Now, I do not want that to be true, either. I would like the UN high commissioner for human rights, who has done very good work denouncing the violations in the Rohingya case, speaking up for the Syrians,—but almost no effectiveness at all. Let's just face it.

In other words, constitutionally sovereign domestic rights regimes are as important as ever, even more important, in a populist majoritarian temper. We need them more than ever. But at the moment, it seems to me that international human rights is a bystander on the story. I would like to be more obliging about it because I teach this stuff, believe in it, and want it to flourish, but it is just not where we are right now. We believed a story that we would be going much farther than we did, and we have not.

Thank you.

JOEL ROSENTHAL: Thank you.

Thanks to the generosity of the Carnegie Corporation, we would like to invite you to a reception, and also alert you to the fact that there are books available for you.