While domestic injustices and the information revolution were key factors, Dr. Telhami argues it's impossible to understand the Arab uprisings without also referring to foreign policy. "The dignity that they sought to restore in these uprisings was not only about their relationship with the rulers, but was about their relationship with the rest of the world."

Carnegie Council's U.S. Global Engagement program gratefully acknowledges the support for its work from the following: Alfred and Jane Ross Foundation, Donald M. Kendall, and Rockefeller Family & Associates.

IntroductionDAVID SPEEDIE: Welcome this evening. I'm David Speedie, the director of the program on U.S. Global Engagement here at the Council.

Over the past year or so, we have had a series of sessions on the greater Middle East and the Persian Gulf. We have heard various perspectives and voices, including the United States, Israel, Iran. Since we deal with U.S. global engagement, the focus perforce has been on U.S. policy and interest in this volatile extended region.

But it is also salutary to reverse the process, as it were. My favorite poet, Robert Burns, whom my friends know I'm very fond of quoting, said that the greatest power that divine power could give us would be to see ourselves as others see us.

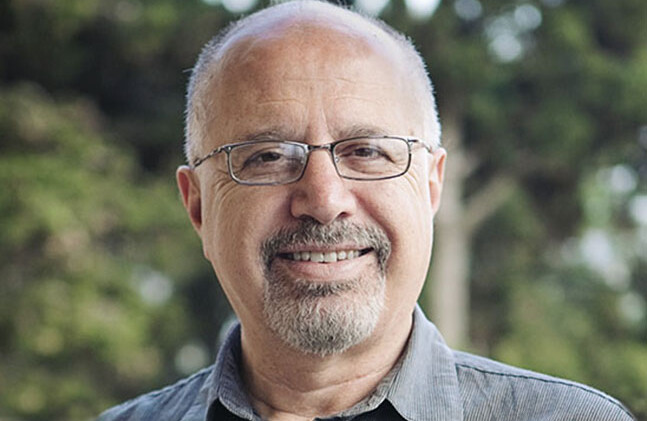

It is important to take on board how the United States is viewed in this case in the court of public opinion in the Middle East. To do that, there is no one better to call upon than Shibley Telhami. Shibley is the Anwar Sadat Professor for Peace and Development at the University of Maryland, College Park, and nonresident senior fellow at the Sabin Center at the Brookings Institution. He has taught at numerous important, leading research universities, including Cornell, where we first met many years ago; Ohio State University; University of Southern California; Princeton; Columbia; and the University of California at Berkeley, where he received his doctorate in political science.

Professor Telhami has also been very active in the foreign policy area outside the academy itself. He served as an advisor to the U.S. Mission to the UN, he was an advisor to former Congressman Lee Hamilton of Indiana, he was a member of the U.S. delegation to the trilateral U.S.–Israel–Palestinian Anti-Incitement Committee, and has served as an advisor to the U.S. Department of State.

Shibley, himself, has articulated this vital nexus of scholarship and policy, perhaps better than anyone else could. On coming to the University of Maryland to the Sadat Chair, he said, and I quote: "I've always believed that good scholarship can be relevant and consequential for public policy. It is possible to affect policy without being an advocate, to be passionate about peace without losing analytical rigor, to be moved by what is just while conceding that no one has a monopoly on justice. This I shall strive to do as the best way to be faithful to the title I now carry."

His passion for peace and his resolve to inform public policy responsibly is advanced admirably through his own rigorously analytic scholarship. His book, The Stakes: America in the Middle East, written in 2003, was named by Foreign Affairs as one of the top five books on the Middle East that year. He has written extensively on the Middle East peace process, on conflict resolution writ large, and is especially recognized as an expert on Arab public opinion.

It is his latest book, The World Through Arab Eyes: Arab Public Opinion and the Reshaping of the Middle East, that he will be talking to us about this evening. Back to the importance of seeing ourselves as others see us, the book covers Arab views of the world, but, as Shibley says in the introduction, particularly of the United States. The book also serves as an invaluable looking glass into the contemporary Arab world. It deals with differences in Arab public opinion from country to country, region to region; and the subtitle, it seems to me, is very important, "Arab public opinion and the reshaping of the Middle East."

Most important for me, Shibley is an old and dear friend. It is my great pleasure to ask you to join me in welcoming him back to the Council.

RemarksSHIBLEY TELHAMI: Thanks so much, David, for this generous introduction.

I thank you all for coming. I see a lot of friends in the audience, people I have known for many years, going back really to the inception of this project.

In some ways, it is very fitting actually that I should do this first book talk in New York at the Carnegie Council specifically and with David Speedie, because the inception of this whole project really goes back to a relationship with the Carnegie Corporation of New York when David Speedie was there, which has funded most of my research for this project over a period of longer than 10 years. In some ways, when you go back to that period—it was right after the 1991 Iraq War—I had just started at Cornell University. My first project was looking at the end of the Cold War and its consequences. That's how we linked up with the Carnegie Corporation when David was there.

But the basic idea that really started me thinking about Arab public opinion—which is, by the way, not a particularly natural thing for me, for someone who started off as a realist in international affairs. I see Carla Robbins here, who was a fellow student at Berkeley, and one of our mentors at Berkeley (not hers I know, nor mine), who passed away recently, Kenneth Waltz, one of the big, influential people in international relations, was known for focusing on states and power and not so much on internal politics. So it's really a bit odd for someone like me to start focusing on Arab public opinion.

But what got me thinking was my engagement with the Middle East during that period, where I was writing about the Middle East, following the Middle East, and in fact had a policy assignment related to the Middle East, just as Iraq was invading Kuwait. What I noticed was that Arab rulers, even though they were authoritarians—and everybody said, "Well, you don't have to worry about public opinion. Who cares? These rulers do what they want and they disregard the public opinion"—so much so that, in fact, the first book that I wrote was on the Camp David negotiations between Egypt and Israel in the 1970s.

When Sadat said at Camp David, "I can't make these concessions; my public wouldn't accept it," Menachem Begin, then the prime minister of Israel, shot back and said, "What public? You shape public opinion. You tell them what they want to hear." Sadat was so angry, by the way, they had to be separated for the duration of the negotiations. They never met again until the agreement was hammered out by subordinates.

But the point is rulers of the Arab world behaved as though public opinion mattered.

We noted, even after the Iraq War in 1991, the seeming contradictions. On the one hand, you had one ruler, King Hussein of Jordan, who was America's top-notch ally. He was dependent on the United States for his political survival. He said no to the United States against joining the Gulf War in 1991 because he believed his public opinion would topple him otherwise. He was prepared to pay the price that came with not joining the United States, despite the fact that he was dependent. On the other hand, you had the king of Saudi Arabia, who seemingly did something unpopular, which is invite American troops on Saudi soil, and he survived.

So what is going on here? It was really at that time that I started thinking about there is something about public opinion that we do not understand, even in authoritarian countries, and we need to pay more attention to it.

The problem is we really didn't have data. What we thought was public opinion was we were interviewing people, elites usually, journalists. We had no idea. We had no confidence in what we were getting back.

That's how I started thinking about putting together a project where we would do systematic public opinion in the Middle East to understand public opinion over a period of a decade. That's the time when the information revolution was starting. The information revolution, particularly the satellite media in the Middle East, the Al Jazeera phenomenon specifically, starts in the mid-1990s.

So I designed the project essentially to have information over a period of 10 years to document Arab public opinion on major issues—foreign policy issues, domestic issues—and document what Arabs rely on for information in the middle of this information revolution. How is this information revolution influencing their opinion and how is it, more importantly, influencing how they define themselves, what I call their identity?

So in some ways, the book is about this documentation, understanding the relationship between media, identity, and opinion over time, how that led to the Arab uprisings in ways that were not understood, and how, since the Arab uprisings, this Arab public opinion is unfolding, what is happening. We have done some public opinion polls since the start of the Arab uprisings.

I am obviously not going to summarize the whole book for you. It is 12 chapters. It deals with themes like Arab identities; the information revolution, Al Jazeera specifically; the role of the Arab–Israeli issue; attitudes toward the United States, toward Iran, toward women, democracy, the rest of the world. So there is a lot in there that I am not going to talk about directly. I want to focus on one theme only today that really relates to the Arab uprisings and what we might be expecting. It is related specifically in this book to Chapter 1 of the book about Arab identities. Let me start with the point I want to make, and then I'll make it with three particular points.

Since the start of the Arab uprisings, particularly in Tunisia and Egypt, we have had an assumption that has been prevalent across the board, that these uprisings in the first place were not about foreign policy, that foreign policy had little to do with these uprisings. Initially, actually, when we talked about the Tunisian revolution, people called it a "food uprising"—and obviously food was part of it. To this day, a lot of the discourse discounts the role of foreign policy in motivating Arabs in the uprisings and their behavior since the uprisings.

I would like to argue that it is impossible to understand what happened and the timing of the uprisings without reference to foreign policy. It is impossible to understand the Arabs' attitudes toward the rulers without understanding their attitudes toward the rest of the world. The dignity that they sought to restore in these uprisings was not only about their relationship with the rulers, but was about their relationship with the rest of the world.

Let me start by making the point that I am not discounting at all that in the first place Arabs rejected dictatorship and authoritarianism and sought a better life for themselves. That is obvious. We have known that for decades.

By the way, among Middle East scholars there was never a question asked, "When will Arabs be angry with their governments?" The only question that had been asked over two, three, four decades is, "How is it that these governments manage to survive despite the anger that we know exists among their public towards them?"

So it isn't that we were shocked by the fact that people were angry with rulers. All the public opinion polls that were done showed that Arabs reject authoritarianism and they do want freedom. Obviously, if you look at the development conditions in the Arab world, they were far behind much of the world by some important measures. Not all countries were alike. So the economics were certainly part of it.

But you have to ask yourself: Why did the uprising happen in 2010 but not in 2005 or in 1995 or in 2000? Because there was nothing at all over the decade preceding the uprisings that you can say that this is an extraordinary economic crisis the likes of which Arabs haven't witnessed before, or this is an extraordinary poverty crisis or food crisis the likes of which Arabs haven't experienced before. You can't even say there has been an extraordinary repression episode the likes of which Arabs hadn't experienced before.

So what has changed that carried people into this revolution? I am going to talk about two things that changed.

One is not controversial at all, which is the information revolution. I think up to a point you really cannot understand the timing without the information revolution, because to the extent that many political scientists and other scholars and analysts didn't predict the timing of the revolution, they didn't predict for one reason, which is they understood that it is not enough to have a lot of angry people to have revolution.

Revolutions are rare in history. Look how many. We still talk about the French Revolution. In the Middle East, there was really one popular revolution only, and that is the Iranian Revolution. So they don't happen very often.

We understood that in order to get from anger to revolution there is a lot of stuff that goes in between. Especially you need mass political mobilization to influence the governments.

For that we assumed you need some political parties, organized social groups, charismatic leadership. That's exactly what governments assumed as well. So they chopped heads. Whenever there was a charismatic leader, they either shoved them in jail or killed them. And they made sure that you don't have political parties that would challenge them. And so people were scratching their heads. How is this anger going to translate into a mass political mobilization?

I think that the information revolution had a lot to do with the genesis of what happened in Tunisia and in Egypt, particularly where, without the need initially for major political parties or well-known leaders, you had incredible ability to mobilize people using social media and relying on the information that was coming from this transnational media that governments had no direct control over.

That happens so rapidly, by the way, it's incredible. Let me just give you a flavor of this. I have a couple of chapters on the media in the book. If you asked people in 2000, "What is your main source of news?" in every country that we polled, which included Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Jordan, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates—in every one of these countries they will tell you that their main source of news was their national media, their national television. By 2010, in every country we asked, every country of those six and beyond, they identified a television station from outside their own boundary, usually Al Jazeera.

The government lost control of the media. You could see that with Gaddafi trying to say on his television "this is al-Qaeda that is doing this" or "this is the United States that's doing this," and Al Jazeera is showing these other pictures. No question that had a lot to do with it.

We saw that social media and the Internet use expanded dramatically just from 2007 to 2010. A remarkable expansion. So that part of it, the social media, clearly is tied to the timing.

But to the extent that there is an impetus to revolt beyond the existing anger that has been there for decades, which is about economics and repression, I want to argue, my main point today, that foreign policy had a lot to do with it, and that you cannot decouple foreign policy from domestic politics in this particular case. Let me make my point through three separate sub-points.

The first is, if you look at that decade and say, "What's striking about that decade, what mobilized people over that decade?" Watch either the public opinion polls that we carried out or look at the coverage of the media or look at the demonstrations that took place across the Arab world for the whole decade.

What were the issues that mobilized the Arab public over that decade? They weren't the economy. What mobilized them was the collapse of the Palestinian-Israeli negotiations in 2000. The bloodshed that ensued after the emergence of the Palestinian intifada and the Israeli operations in the West Bank galvanized the public even before 9/11 and continued to galvanize the public post-9/11. Then America's reaction to 9/11, which many people saw as an assault on the Muslim world—the war on terrorism and the war in Afghanistan, but especially the war on Iraq that we have documented had dramatic influence; then in 2006 the war between Israel and Hezbollah; then in 2008–2009 the war between Israel and Hamas. Those were the major events that galvanized public opinion and anger over the years.

Here is the differentiating story on this issue. On almost all these issues, the governments in the Arab world were on the other side of the public, starting with the Iraq War, where 90 percent of the Arab public thought the war would go against their aspiration, and yet the governments acquiesced, or, even worse, were seen to be collaborating with the public's enemy on this issue. On the Hezbollah–Israel war, the public was with Hezbollah and the governments were against Hezbollah. On the war with Hamas, the governments were against Hamas and the public was with Hamas, and that was particularly true in Egypt.

Foreign policy was central throughout the decade. It is inescapable. You can see it as the main feature that got the public more angry. That's number one.

Number two, we have a lot of evidence from the polls on this. That evidence is somewhat indirect but telling.

Let me give you an example. One of the questions that we asked over the years is, "Whom among world leaders you do admire most outside your own country?" Obviously, we don't want them to say they don't like their own rulers. We asked this question every single year, not because I assumed that people really knew world leaders. I just wanted to understand what is the framework that they are using when they are identifying a particular ruler, what is the prism through which they are looking when they identify a particular ruler. Let me give you a sample of the rulers who were identified as the most admired rulers in the Arab world over that decade.

Let's start with 2002–2003, just around the time of the Iraq War, and 2004 in particular. Remember, this is the time when here we are talking about the clash of civilizations. This is post-9/11, when we are saying that our policy, our relationship with the Muslim world, is something of a clash of civilizations. You have advocates for that in the Arab and Muslim countries as well. Obviously, people had a stake in this being a clash of civilizations.

Well, the most admired leader during that period in the world was Jacques Chirac of France. I needn't tell you about the history of France in the Middle East, and I needn't tell you about the recent history of France vis-à-vis the Middle East immigrants, and I needn't tell you about what was on the news pertaining to the veil in French schools. So why in the world would they, of all—they don't mention any Muslim leader or religious authority, including Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who was preaching on Al Jazeera. They mention Jacques Chirac.

Well, Jacques Chirac was the man who hosted Yassir Arafat to die in France as a head of state when he was being ostracized, and everybody was focused on that issue. And he was seen to have stood up to George W. Bush on the Iraq War. So he gets rewarded.

The next, 2005–2006–2007, it's not Jacques Chirac anymore. Now, I want you to think about that period, what is happening in this period. This is now post-Iraq War and we have the ugly sectarianism of Sunni/Shia. How many people have written that this now is a Sunni/Shia divide in the Muslim world? We are seeing some of that obviously, and some of it is legitimate. But the reality of it is people are focused on the Sunni/Shia divide in the Arab world.

We are asking in these six countries, "Whom among world leaders do you admire most?" We get Hassan Nasrallah of Hezbollah, the Shia leader of Hezbollah, in Egypt and in Morocco and in Jordan, majority Sunni countries, right in the middle of this. Why would they say Hassan Nasrallah, particularly where we are talking sectarianism? Because he was seen to have stood up to Israel and the United States in that war in 2006. That's the reason why they selected him.

In 2008–2009—this is right after the Gaza War—Hugo Chavez. Now, what do people know about Hugo Chavez? They don't know much about Hugo Chavez. But they knew one thing, is he's the only leader in the world who cut off diplomatic relations with Israel over the Gaza War. That was enough to say Hugo Chavez is the man they admired.

In 2010, just before the Arab uprisings, we start having the first Sunni Muslim leader, and that is the currently besieged prime minister of Turkey, Erdogan. He is there in 2010 and he is there in 2011. You finally say, "Okay, we finally got it. They are choosing a man who represents Islamic democracy, not foreign policy anymore." I'm sorry. It doesn't work that way. Let me tell you why.

First, Erdogan had been in power one way or another for the decade. Why didn't they recognize him in 2005 or 2007? Why wait until 2009–2010? I mean it's not like suddenly he became more democratic. In fact, if anything, he was probably becoming less democratic. So what is it about him? Well, it happened after the Gaza confrontation, when Turkey took an anti-Israeli position, and he was being rewarded.

In fact, by the way, this is interesting about Turkey. It's now in the news. We are talking about not just Erdogan himself, but Turkey. In some of the polls that we have done on democracy in the Arab world, particularly in Egypt, Turkey is a model. More frequently Egyptians identify Turkey as the country they want their country to look like most. When you ask them, "Which country do you want your country to look like most?" they identify Turkey.

But here's the thing about Turkey that you should think about for a minute. When we ask people, "Name the countries that you think are most democratic in the world" they don't name Turkey. They name France and they name Germany and they name Sweden and they name the United States—all Western countries. Turkey doesn't show up in the top five, or even ten, countries as most democratic.

But when you ask them, "What do you want your country to look like?" they say Turkey, because the truth of the matter is they like Turkey because they want democracy but they want a lot of other things. They want democracy and Islam for one thing, but they also want prosperity. They don't say Pakistan or they don't say Bangladesh. They think Turkey is prosperous, and they want a country that stands tall in the world. Without that standing tall in the world, they wouldn't like Turkey. If Turkey had been in 2010 a close ally of Israel or had condemned Hamas in the war, there's no way Turkey would have been identified, despite its democracy.

So it's all these things that they want that are part of their identity. It's not just one thing.

One final example about rulers. This is kind of striking. A year after the uprisings—and now we are in a period of hopeful democracy—there is a lot of optimism, particularly that year, in the Arab world. People obviously want to get rid of authoritarian rulers. In Saudi Arabia and Jordan, we asked this same question, "Whom among world leaders do you admire most?" The person that we get is somebody we hadn't gotten on the list at all in the past in those two countries, Saddam Hussein. This is unprompted. We don't give them names.

Why Saddam Hussein? Because at that time people are focused on the mess in Iraq that is troubling: the rise of sectarianism, the role of Iran rising, anger with the United States and their military presence. It's like "in your face." Saddam Hussein, instead of saying some Democrat or something.

So foreign policy is on their minds. Foreign policy frames their attitude. Foreign policy is part of their anger. Foreign policy is the added value that increased the anger over that decade. The third point I want to make goes deeper than those measures. It has to do with how identity has shifted over the past decade.

In the end, identity is really, really important in my own judgment, because it expresses a set of aspirations that frame opinion. Opinion in some way changes up and down, but it is constantly reflective of a framework that is dependent on that core identity that people have.

What we mapped out in the project was trying to find out how people's notions of identity are shifting, particularly as a function of the information revolution. We all understand that identity is complex and there are multiple identities. You can at once be an Arab and a Muslim and an Egyptian and a Jordanian—you can be all these things, and we don't take that away from people when we ask the question. In fact, I start by telling them I recognize they can be all these things. But I ask them, "Which of those things are more important to you today—your Islamic identity, your Arab identity, your Egyptian identity, your Jordanian identity, citizen of the world?"

We traced how it evolved over the decade. And mind you, there are variations from country to country. It's not all the same. For example, the Lebanese have the strongest identification with the state. This might surprise you for a sectarian country. I see Jack Snyder there. I bet you he has a theory about why that is the case, and it's probably right too. In Saudi Arabia, they have the weakest state identity of all. In Egypt, they have the most balanced identity between Egyptian, Arab, and Islamic. So there are differences.

But aggregately, over the decade, one thing is clear: identification with the state has declined. Let me give you three reasons for that, some of which we document.

Reason number one is somewhat speculative. That is that I believe that in the Arab world what you have is when people refer to "the state"—the term A'dowlah in Arabic—they also refer to the rulers and the government. It is very hard to differentiate the ruler from the state, particularly when that is all you know. As you know, most of the rulers, whether it was Mubarak or Gaddafi or the royal families in Saudi Arabia and Jordan, have been there for the duration of most people's lives. They know nothing else. So the state is the rulers.

If you are not happy with the rulers, you are less happy with the state. I'm exaggerating. It's not that they are fully identifying, but there is a confusion. Particularly in Saudi Arabia, where I said it is the weakest, it is built into the name—it's Saudi Arabia, it's for Al Saud, the royal family of Al Saud. In Jordan it's the Hashemite Kingdom of Al Hashem. It's built into the state. So the more dissatisfied people are with the rulers, the more dissatisfied they are also, the more uncomfortable they are, with the state.

The second reason is that the information revolution had an impact. We found definitely a correlation between the transnational media that reaches all Arabs and how people identify themselves. Obviously, the logic of this new media—particularly Al Jazeera, but other Arab satellites—is that their consumer was no longer the local consumers, no longer the Qatari or the Bahraini; it is now "the Arab" and "the Muslim," because they are trying to reach everyone who can speak Arabic, and that is 350 million people. So when they put the product on television, they are appealing to the widest possible audience. Therefore, it was bound to reinforce these broader identities. There is more sharing of ideas.

Now, there is a lot of self-selection. So Al Jazeera's success initially was because that's how people felt. But over time there is reinforcement. We found that there is a factor that we call the "new media" that is impacting, strengthening people's Islamic and Arab identity at the expense of the state. That's number two.

Number three, I happen to believe that, to use someone else's language, if you have an identity that is threatened, then you rally behind it. We find, in part, that the expansion of Islamic identity over the decade is not merely a function of Islamic groups being effective, but also a function of people's sense that Islam is under assault post-9/11. Therefore, when they assert that they are Muslim, it's not necessarily saying they support Islamist groups, or even that they are religious, but very often saying, "We don't have to apologize for who we are." As I said, it is like you are what you have to defend, and they had to defend that part of their identity in part. Therefore, there has been an increase in that identity as well over time.

Now, granted that when people say, "I am an Arab," or, "I am a Muslim," it could have multiple meanings that vary depending on context. I discuss that because I think an Arab could say something else to a fellow Arab and something else to a Westerner when you ask them about their identity.

But here is the thing that is consequential. It doesn't matter exactly what you mean when you say, "I am an Arab," or, "I am a Muslim." When you say that that is your primary identity, you are connecting yourself to people outside your own boundaries. If you are an Egyptian and say, "I am an Arab first," then you are connecting yourself to the Lebanese and the Jordanians and the Saudis. When you say, "I am a Muslim first," you are connecting yourself to the Pakistanis and to the Afghanistanis.

That has consequences for what they believe and what they think their governments should do. In fact, here is a follow-up question that tells you a story. I ask "Do you believe that your government should serve the interests of its citizens or the interests of Arabs or the interests of Muslims beyond its boundaries?" We get half or more who say it should serve the interests of Muslims or Arabs outside their own boundaries. They think the role of the government that represents them, which is usually representative of citizens, is to serve the interests of Arabs and Muslims outside their own boundaries. That puts foreign policy center stage. It's impossible to decouple it.

So I fully understood, when I was there in Cairo just a few days after the revolution, when I went to Tahrir Square to one of these thousands-of-people demonstrations where people were chanting very loudly—mesmerizing really; it gave me the shivers—"Raise your head high, you're an Egyptian! Raise your head high, you're an Egyptian!" The same thing was repeated in Libya. I understood that they weren't raising their heads, and that wasn't just because they weren't raising their heads vis-à-vis their governments; they didn't think their governments were raising their heads vis-à-vis the rest of the world. The two are connected. You can't break it down. You can't decouple it. It's very central.

I am going to end by offering you just two brief reflections on where we go from here, particularly with the Arab uprisings. We can come back to foreign policy. There is a lot on foreign policy, as well as domestic politics, in the book. But I want to just offer a couple of reflections from my conclusion about what it means for the Arab uprisings.

I think in the end, if you ask me what is new in the Arab world today; is this a cyclical uprising that is likely to fade, just like many uprisings we've had before? I would say no, it's not. I think it is a profound change.

I think it is maybe less understood. We talk about it, but we don't fully grasp it. I believe that we are witnessing a public empowerment the likes of which we have never witnessed before. I compare it, perhaps not in a parallel way, to the Industrial Revolution, where the economics changed for all of the individuals by virtue of earning wages and created completely new politics in which the individual played a role.

Today we are witnessing an information revolution that does empower individuals and groups that had never been empowered before. And that is an information revolution that is only expanding; it is not going backward. Therefore, we have an empowerment on a new scale that is likely to stay with us for the long haul.

But the consequences of that are not fully understood. This is not the end of politics. It's merely the beginning of new politics. It was never the case that public opinion alone shapes politics anyway, even in democracies. It is just that we have a new element in our politics.

The empowerment of publics doesn't also tell you much in and of itself, because which segment of the public? When we talk about "public," you are empowering left and right, rich and poor, secular and religious. The more diverse a society is, the harder it is to predict both where the public is or how the politics will unfold.

But we are at the beginning of a new politics. There is no doubt. If you are going through it, it is very painful, as the Egyptians or the Libyans or the Tunisians see it. But I see it, in historical perspective, as definitely a move forward.

Thank you very much.

QuestionsQUESTION: Sondra Stein.

Could you say something about Syria now, with Hezbollah and Sunni/Shia problems, as best you can project?

SHIBLEY TELHAMI: Yes. I had breakfast with a friend who is watching this and asked me the same question. I said I'm probably one of the most opinionated people in the world, except I have no opinion on Syria.

In some ways I mean it, because I think if—this happens too when I am asked by officials in Washington about "What do you think we should do?" I know what we shouldn't do, but not exactly what we should do. But let me just say two things about what is happening in Syria and my instinct about it.

First, recall what I just said about the empowerment, that the more diverse a society is, the more complicated that empowerment is, obviously. So what we have in the particular Syrian case—it started, more or less, around a similar uprising against an authoritarian regime, undoubtedly. The Arab public sympathizes with the rebels against the government. They see Assad as being another one of the Arab authoritarians.

Very quickly it became much more than that, which is it became an ethnic conflict between Alawites and Sunnis and Druids and Christians. So you have that complexity of it, secularist and religious.

It became an arena for other groups from the outside, including Islamists groups that saw it as an arena to fight. Layered over that, intervention of foreign players, all of whom have a state in the outcome, and that includes Iran and Turkey and Hezbollah and Israel and the United States and Jordan. And then, layered over that you have this refugee spillover that is complicating politics even more and blowing back into Syria as well.

Because of this international dimension and the ethnic dimension, in some ways the conflict isn't limited to Syria anymore. Boundaries have disappeared in this fight, particularly along the Lebanese-Syrian and the Iraqi-Syrian borders.

So it is very, very complicated and very difficult to know what the outcome will be. It will be very difficult to know what to do.

But here is the thing that keeps me from supporting American military intervention. And I'm torn over it, because when you watch 80,000 people dying and atrocities now on both sides, it is very hard to not want to see intervention. I was on the board of Human Rights Watch. It is an issue I care about deeply. I am a loss sometimes.

But I look at two things. Number one, where people are in the Middle East. I see the following. In the polling that we have, 90 percent of Arabs that we poll, including in Egypt, say they support the rebels against the government. But when you ask them, "Do you want to see foreign intervention to topple Assad?" a plurality say no. That is also the position of the president of Egypt, Morsi, who is a Sunni Muslim from the Muslim Brotherhood. The Muslim Brotherhood are among the rebels against the Syrian government. They don't want to see it.

In fact, in retrospect, in my polling when we look at Libya, we find that in retrospect the majority of Arabs think that supporting international intervention in Libya was a mistake. They don't trust the West. And, frankly, there is not a very good record for knowing what to do if you intervene. So that's one thing that keeps me from even contemplating it.

But second, I find it a little strange, to be honest, particularly from some of my colleagues, who were so opposed to George W. Bush's intervention in Iraq, over the basic notion that you need international legitimacy when you intervene militarily in a place where the outcome is going to be more consequential for those locals and neighbors than it is for you. At least you have essentially taken it upon yourself to decide what is the moral thing to do.

If you can't persuade the international community to be on board over a moral issue, and you are prepared to pay the price, you say, "I am going to send my own soldiers, I am going to pay my own money"—if you can't do that, then we have to think about it more than once. We can't, just because we like Obama better than we liked Bush or Bush more than we like Obama—we should go with the same principle.

So I think personally, despite all of the issues, I believe that the president has been right to be reluctant to intervene directly.

I think when you look at the emerging competition between the United States and Russia, with Russia asserting itself a little bit more, you can imagine what might happen if in fact we did intervene against their wishes, how that would be consequential to the rest of the international community.

So it is frustrating. But I think the frustration, as I see it, is—if you look at the period since World War II, where we had a huge degree of globalization, particularly in information, where we see what is happening in Syria almost instantly and we see the pictures, the bloodshed, we know the names—and there are certain expectations, where we or the Europeans or the international community has expectations about what needs to be done.

In 1982, when Assad killed several thousand people, nobody saw it. It was only reported afterwards. There was no urgency to intervene. Now there is this urgency to intervene. I see no parallel transformation of international institutions to accommodate this rising expectation of the public. I think that is something that is depressing about the state of international affairs. But it is not, per se, a failure of American foreign policy.

QUESTION: Warren Hoge, International Peace Institute.

This is the 20th anniversary, as you know, of the Oslo peace process. When that peace process began, the conventional wisdom was that in order to solve the overall problem of the Middle East, you had to solve Israel–Palestine. Then, when the Arab uprisings happened, there was a counter-feeling, that "Wait a second. That's not what's motivating these people. It is their own domestic situation."

I've listened closely to what you've said tonight. I want to ask you in light of that: Do you think that the old argument, that solving Israel–Palestine—which is an interesting consideration right now, because it's far from happening, and yet you have an American secretary of state who is pressing very hard for that—do you believe now in the earlier thought that solving Israel–Palestine is essential to solving larger problems in the Middle East?

SHIBLEY TELHAMI: I have a chapter in the book called "The Prism of Pain." The prism of pain is the Arab–Israel issue, particularly the Palestine–Israel issue.

I never believed that the core of the social and political problems in the Middle East is the Arab–Israel issue. Of course it is not. We have lack of development in Sudan or in Algeria, and you can't tie it directly to the Arab–Israel issue. So it's not that, even though it's a complicating factor sometimes, particularly for neighboring states for sure, for states that have been engaged in war, that had spent a lot of money on that, that have suffered and paid a price. So for Egypt and Jordan and Syria and Lebanon and the Palestinians and Israel, it has been part of their problem, because that's their lives, and the wars and the economy have been very much tied into it.

But I think what is misunderstood about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is that it is the automatic prism that Arabs use when they look at the world, particularly the United States, that it is impossible to understand how they evaluate a foreign leader or a country without tying it to the position of that leader or that country to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Most of what we see in the trends of anger toward the United States, for not just the past decade but really two decades, dating back to the 1990s, shows that the anger with the United States is very much tied to the Arab-Israeli issue, where it spikes and goes down. It wouldn't disappear if that goes, obviously.

But I want to read you a couple of paragraphs from the book that are related to the role of this. There is a lot of data here over a period of 10 years showing how Arabs rank it so high in their priorities and why, and why it matters to them. Frankly, in some ways, I am surprised that people are surprised that it is tied to the perception of the United States.

If you look at American foreign policy and Israeli foreign policy, the motto is there should never be space between Israel and the United States, projecting Israel and the United States as being identical in their position. So if people are angry with Israel, of course they are going to be angry with the United States. It just goes without saying. In some ways, it is the success of this projection of no space.

But it goes far deeper than that. Let me read you two paragraphs that go beyond the data:

"For Arabs, the Palestinian–Israeli conflict still embodies collective historical and psychological experiences that are integral to the way they view the outside world. The conflict represents not only the painful experience of Arabs losing Palestine in 1948 and facing another devastating defeat in the 1967 war; it is also a reminder of the contemporary Arab history, full of dashed aspirations and deeply humiliating experiences, usually tied to the West. Since 1967, Israeli control of East Jerusalem, a city that symbolizes an even older painful conflict dating back to the time of the Crusades, has added fuel to the fire.

"But what distinguishes the Palestinian-Israeli conflict from other painful experiences is that it is seemingly unending, with repeated episodes of suffering over which Arabs have no apparent control. This is an open wound that flares up all too frequently, representing the very humiliation that Arabs seek to overcome. If the Arab Awakening is in the first place about restoring dignity, about raising Arab heads high in the world, then the Palestinian-Israeli conflict represents dignity's antithesis."

Now, this is one thought I want to leave with you. But there is another thought that I think is even understood less.

"There is one other way in which the Arab Awakening has raised the importance of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in public priorities.

"A good place to start is Israel's sense of deep insecurity. Without Palestinian-Israeli peace, Israelis know that war with Arab parties will remain possible. For Israel, this means it must plan for every contingency of war with the Arabs, and even with non-Arab states, like Iran. The net result is that Israelis feel that their security requires strategic and technological superiority over any combination of Middle Eastern states, especially Arab. On this they have the unreserved support of the United States and complete assurance from Congress and the White House that Israel will receive all the technological and military assistance it needs to keep its superiority and that Arabs will be denied similar capabilities.

"There is near-consensus on this in Israel as well, regardless of the political outlook on matters of concessions to the Palestinians. But, seen from the Arab side, this Israeli imperative, seemingly driven by security, entails exactly the sort of dominance that they reject and are revolting against, the very essence of the prism of pain through which Arabs see the world.

"In an era of Arab awakening, half-a-billion Arabs and Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa find it impossible to accept the strategic domination of a country of 8 million, especially when they don't accept the Israeli narrative for the absence of Palestinian-Israeli peace to begin with. And they see America, and to some extent other European countries, as providing the support to make it possible.

"This ensures that, at least so long as Palestinian-Israeli peace is absent, Israel and the Arabs are condemned to a relationship of confrontation and occasional war for years to come and that American-Arab relations will always be caught in the middle." Will always be caught in the middle—no escaping that.

One example of this—just think about this—we are in the middle of a horrific civil war in Syria. Israel is only a bystander in some ways. It has gotten involved a little bit, but it is not about Israel at its core. We see the sectarianism. It is said that maybe 80,000 people have been killed.

Well, the largest demonstration, just two weeks ago in Egypt, generated by a Muslim ruler and the Muslim Brotherhood, the largest demonstration on foreign policy they have held since the revolution, was not to protest the killing of 80,000 people; it was to protest the Israeli attack on the Syrian facility. Just think about that for a minute and tie it to what I said earlier.

QUESTION: Ali Mazzara with the State University of New York Global Center. I'm here with 20 young women who are pursuing careers in international relations and global affairs.

If they want to learn more about an Arab perspective of the Middle East, besides your books, what books would you recommend? And also, if they wanted to go into public diplomacy, what suggestions would you give to them as they begin their careers?

SHIBLEY TELHAMI: There are a lot of really good books, particularly recently. I think what happened over the past 10, 20 years—and I have to say, in part, thanks to the Carnegie Corporation of New York, that have actually supported a lot of that research—we have a new group of young scholars who are very, very talented, and you are beginning to see a lot of good writings on the Middle East. There are a lot.

But I want to address the issue that you suggested on public diplomacy. Something I care about personally—I served on two commissions. I served on the Council on Foreign Relations Commission on Public Diplomacy and then on the Bush administration's commission, a nonpartisan commission to study public diplomacy toward the Arab and Muslim world, and we wrote recommendations, a little book actually, on what needs to be done.

But I want to say that in just the beginning of that report we made it clear that we believed that most of the attitudes of people toward the United States, particularly Arabs and Muslims, were not tied to any public diplomacy; they were tied to hard policies.

You can affect it on the margins. Over the years, we found a couple of things that really are very telling.

Language—Americans who know Arabic tend to be more understanding and sympathetic; Arabs who know English tend to be more sympathetic. Language matters.

Exchanges matter more than anything else, more than anything that you can say.

But what doesn't work—and I show that in the book—I even went to the extent of writing a chapter called "Empathy and Incitement and Opinion," which was partly based on that experience, partly based on a committee I served on that David mentioned, called the Anti-Incitement Committee. How do you fight incitement?

With the polling that we have done, it is very clear that these attitudes, the absence of empathy, they cannot be changed simply by telling a positive story about the other side. It just doesn't work. If you are in the middle of a conflict—I know in the Bush administration the first thing they did was they brought an advertising agency executive and appointed her to head this Office of Public Diplomacy. She had no experience with the Middle East. A wonderful woman, I'm sure brilliant at what she did. But the idea that they are going to go out there and put positive images and you are going to change people's minds just doesn't work.

We found that it does exactly the opposite, that people become more resentful when they see that information that is positive about the other side. We experimented particularly with looking at how Arabs view Israelis and how Israelis view Arabs, how they view footage that is positive of the other side, and also how they react to civilian casualties of the other side.

The evidence is that conflict frames these attitudes far more. It is very simplistic to think that you can fight incitement through some public diplomacy.

QUESTION: Krishen Mehta, Aspen Institute.

I have a two-part question, sir. One is that through your surveys we have a better understanding of Arab views and opinions and you have the Anwar Sadat chair of peace and development. I am wondering to what extent have these surveys affected American policy, American media, American public views, so that the objective of peace can be furthered, not only in the United States but in the West.

My second part of the question is relating to your comment that the government has lost control of the media in many countries. Does it mean that we will have a Moscow Spring and an India Spring and a China Spring in the future, if people are much more connected to the media in these ways, as evidenced by your surveys?

QUESTION: Tyler Beebe.

I just wondered what your sense was of Arab public opinion about Iran's intention to develop nuclear capability.

SHIBLEY TELHAMI: Just as a matter of information, the bulk of this book, of course, is Arab public opinion, because I have 10 years of public opinion polling in the Arab world. But actually, it also includes Israeli public opinion, Jews and Arabs in Israel—I do it to control, to compare, particularly on identity issues and on issues that bear on the relationship—and of American public opinion.

So we have a whole chapter, called, I think, "From 9/11 to Tahrir Square: The Arabs Through American Eyes." So we do a whole analysis.

I did public opinion polls. Actually, I've been polling Americans on the Middle East also for almost two decades, dating back to the 1990s. Some of that is in here to compare and to see what impacts American public opinion as well, and whether the Arab uprisings have shifted. There is evidence that they did. Whether it is profound or not, it is hard to tell yet, but there is a shift, and we know that is coming.

Tied to that, the issue of Iran, there is a whole chapter on attitudes toward Iran. It's interesting when you look at the Iranians' nuclear program. I know there is a whole view that Arabs are onboard, possibly even for launching an attack on Iran or feeling threatened by Iran's nuclear program. And I'm sure some Arab governments are, particularly the small ones in the Gulf who have to worry about Iran.

But Arab public opinion is far more complex on this. One of the things that is fascinating is when you ask them to name the two biggest threats to them, an open question, roughly 80-plus percent say Israel first, another 70-plus percent say the United States second, and roughly between 10 and 20 percent say Iran third. So Iran is third, but it is third, not first.

But here is more telling. When you ask them, "Do you want the international community to pressure Iran to stop its nuclear program?" you have a majority in every country saying no. That includes Arab citizens of Israel itself. It tells you something about how people frame these questions, how this whole issue is part of a framework about what is the threat in the region and what the relationships are. So that is particularly telling, I think, about it.

Are the Iranians themselves trying to develop nuclear weapons? When I ask public opinion in the Arab world, by the way, they go back and forth. Now a majority thinks yes.

I, as a scholar, think probably yes, because, as somebody said, you can make a case why it might be wise for them to do it. But I'm divided on this as well, because I see some downside for them to do it. So I don't take it for granted that that's what they are doing. I think that, therefore, keeps some space for diplomacy.

As for the question about a possible India, Russia, or China Spring, it's interesting you say that, because right after the Arab Spring I wrote this piece about public opinion and the media and its relationship with the Arab uprisings, and I got an invitation from China to go talk about that. Privately, the question was, "Do you think it could happen here?" Clearly, people are watching this issue.

I don't believe that every country is the same in the way these things work out. But I do believe that public empowerment, individual empowerment, is coming to China, as it is everywhere else. What you can't do is predict how it is going to unfold. But I have no doubt that people are going to ask for a piece of the pie and more power as a result of this revolution.

I don't think any country is immune. By the way, I don't think any country is immune in the Middle East, including the rich countries. Anyone who thinks that wealthy countries can buy their way out of it I think doesn't understand the game.

I'll give you one final example. Last fall I was in Saudi Arabia. I went to a women's college. I met with the director. And by the way, there are more women students in colleges in Saudi Arabia than there are men. The problem is getting jobs afterwards. But, just like here now, they have more. But they are exclusively women's colleges.

The director said that a lot of these women come from sheltered homes, with very little experience, and they first thing they do the first year is train them how to research, including using the Internet for research, and by the end of the year they start Tweeting. She monitors their Tweets. They start asking about power and corruption and their piece of the pie. It's just inevitable. I see it at every level in every country.

DAVID SPEEDIE: As we conclude, every rich session has some what we call takeaways. There are at least two.

One speaks to one of Krishen Mehta's last points, about the hope that somehow this copious and painstaking and long-range research that you've done, Shibley—that the policy access you have had, that this somehow is feeding into the policy circles where it's important. That doesn't mean that the view from the Arab street, which is not always reassuring and not always comforting; it also doesn't mean that we recalibrate or change our policy. But it is very important that we know this.

The second is, if I may just quote the last two sentences of your book: "Even as many Tunisians, Egyptians, Yeminis, Syrians, and other Arabs try for a better life and more freedom for themselves at home, their aspirations remain connected to the aspirations of other Arabs and Muslims and to a vision of their collective place in the world. Above all, they want to hold their heads high."

In other words, these phenomena, these revolutions that you say are rather unusual, they weren't accidental. There was a new media engine that was driving. But there is an awareness, as you say, of transcending national boundaries that is very important for us to understand.

Thank you so much.

SHIBLEY TELHAMI: Thank you.